The Prisoner and the Fugitive by Marcel Proust

The volume inclined to make you wonder most about your own lost time

Status: Available

Finding Time Again by Marcel Proust

The best of the bunch

Status: Available

LIKE MOST PEOPLE WHO HAVE READ “IN SEARCH OF LOST TIME,” I initially bought the books because I thought it would look good to have them on my bookshelves. I mean this in both a literary and literal sense.

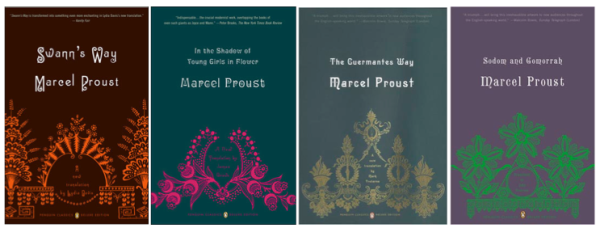

In 2002 Penguin Classics began publishing new translations of the six-book novel, and the Penguin Classics Deluxe paperback edition of “Swann’s Way” was, and is, one of the most gorgeous covers I have seen on any book. I bought it, along with the next three books, deceiving myself that my purpose was the reading of a classic work when, as Proust himself would likely have seen, the honest purpose was more or less the display of beautiful books. Fortunately, publishing company art departments have gotten so adept over the years that in many cases you can, and should, judge a book by its cover. So it was with Proust.

There is, however, one catch. Should you get hooked on the first four volumes, copyright law in America prevents you from getting the final two stateside until at least 2018. (According to slate.com, we have Sonny Bono to thank for that.) I was content to wait, and then one day a surprise package arrived from a good friend. Inside were the UK editions of the last two volumes. Even though they don’t have the beautiful covers of the American editions, I thought it was only right to make them available to you.

“The Prisoner and the Fugitive” and “Finding Time Again” are the final installments of the new translation of Proust’s novel. The books are sprawling, orotund, and contain the amount of tedium you might expect in hundreds of pages about Paris’ idle rich at the fin de siecle. Proust’s narrative is heavy on winding internal monologue and light on external events, meaning he will spend several pages exploring the various interpretive and expressive effects of a man deciding to wear a monocle, and then use a single, offhand sentence to inform you that the hostess of the party where the man with the monocle was observed died not long after the event. And yet, all these things contribute to the gifts of the novel, which is stunning in the beauty of its writing and its insight into human interactions, tragic and tender in its regard for the handful of characters who shape the narrator’s world, and just generally unlike anything you will ever read.

Also, the books are long. I managed to tackle all six in just a shade under a decade. But this, too, is part of the charm: a story about the passage of time benefits from a long reading period.

With all this in mind, it is not recommended that you start with “The Prisoner and the Fugitive.” One reason early translations may have been incorrectly titled as “Remembrance of Things Past,” is because the novel itself is about just that. Proust makes almost constant reference to previous events and characters as the story progresses, and in “The Prisoner and the Fugitive” we encounter the final stage of the narrator’s love affair with a woman named Albertine, which began in book two, paused in book three, resumed in book four and continues here with her as his “prisoner,” kept in near captivity at his Paris home.

The story is mostly focused on the narrator’s jealousy and Albertine’s suspected unfaithfulness, a subject covered similarly in the first volume, “Swann’s Way.” It is, to my mind, one of the most monotonous portions of the entire novel. The narrator alternates between tepid affection for Albertine while she is there, and searing misery when her absence allows the narrator’s imagination to envision her betrayals. There is a deeper subtext in which the narrator himself is the “prisoner” of his love, and then, following Albertine’s death, the “fugitive” as he tracks the internal healing process that allows him to escape his grief and forget her. Nonetheless, it all took me many, many months to trudge through. On the other hand, many reactions to this portion of the story, what is known as “The Albertine Cycle,” are that it contains the richest sections in all of “In Search of Lost Time.” It is true that no one does jealousy like Proust.

“Finding Time Again” is the last book of the novel, and is in close contention with “Swann’s Way,” the first book, for being the best of the six volumes. It may be the liberation from the endless cycle of the narrator’s disinterest and agony of the previous book, or the fact that external events like World War I flesh out a framework of actual plot; it may be that the final volume is the most referential of all the previous pieces, putting forward an all-star cast to reward your patience and attention, or it may also be that this is the single volume in which the narrator is compelled by a larger purpose than his own leisure, finding his calling in art and writing. It may also simply be that you are so close to the end that your interest is renewed, but I honestly don’t think that is it.

In “Finding Time Again” the narrator’s memories are the most vivid, as are his interactions. Rather than 40 pages on trying to go to sleep as a child, or a long train ride that sets the stage for a laborious etymology of French place names, Proust wanders the unlit streets of World War I Paris, encountering a changed city. He attends a party in which the end of an age is made apparent by the decay of the once robust people who have been part of the story until now. His understandings of Time and Habit and Death, first illuminated by the madeline in the first book, are fully revealed and provide the narrator with his vocation. This final volume presents the organizing principle of the entire work, and imbues the previous five books with the glow of Proust’s own feeling.

In short, it’s so good that I instantly wanted to begin again at the start, and take the whole 3000 page trip again. And someday I will.

Do you want to trade paperbacks?

This will be the last post for a while as I step away from my blogging duties to get married. In keeping with today’s theme, I leave you with a reminder of the joys of French culture to encourage you to read Proust and tide you over in my absence.

[…] Marcel Proust […]

Some visual aids for the Proust universe:

http://resemblancetheportraits.blogspot.com/

[…] book about aging, identity and remembering. In subtext, the story is about much of what Proust wrote about (Egan quotes him at the opening of the book). In actual text, “Goon Squad” […]

[…] book about aging, identity and remembering. In subtext, the story is about much of what Proust wrote about (Egan quotes him at the opening of the book). In actual text, “Goon Squad” […]