A FEW DAYS AGO, I read Christopher Hitchens’ Vanity Fair article about the physical pain of his treatment for esophageal cancer. It is one of the several extraordinary essays he composed about what turned out to be the final chapter of his life, and this latest (and last) piece described a bedridden agony that sounded like every hang over I’ve ever had combined with every sickness I’ve ever experienced, complemented by the prospect that, though it may stop at some point, it was not likely to get any better. When I woke up far too early this morning after being out far too late on a week night, the article came to mind: “I lay for days on end, trying in vain to postpone the moment when I would have to swallow. Every time I did swallow, a hellish tide of pain would flow up my throat, culminating in what felt like a mule kick in the small of my back.” Laying in bed with my aches and grumbles, I thought to myself, “Well, I probably still feel better than Hitchens does.” Then I read the news and realized that I didn’t. Or that I did, perhaps.

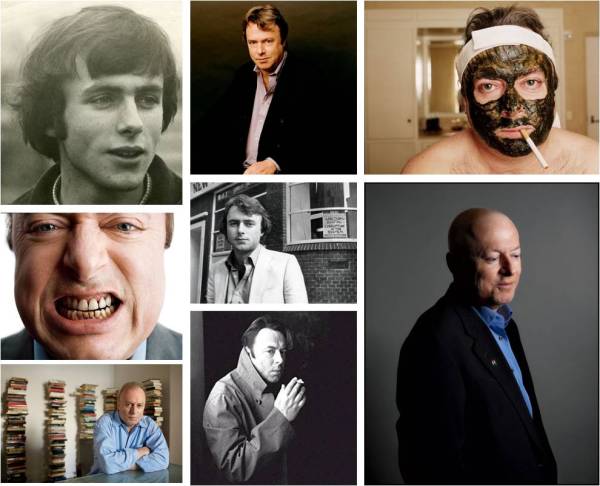

Like every remembrance about Hitch, this one will include the obligatory “I didn’t agree with everything he said,” along with the almost-as-frequently-made point that the bulk of my disagreements centered on faith. To be clear, I rarely disagreed with Hitchens on the bad behavior of religious people and religious institutions. My biggest dispute was his apparent belief that the failings of believers was evidence for atheism, which is exactly the opposite of where I end up examining the same issues. That said, I was glad for his vocal disbelief for the simple reason that he called on religious people to prove themselves again and again, and that is rarely a bad thing. And he was an incredibly good sport, as can be seen in his willing appearances on Christian radio, at Christian book fairs and in respectful debates at Christian schools. Hitchens cultivated the image of a polemicist or contrarian or some kind of roguish villain (the Alan Rickman of American Letters, as I am fond of saying). But spend some time with his books (the ones that aren’t directly attempting character assassination) and you may be surprised at how many things he praised and genuinely enjoyed.

Questions about the possibility of life after death are rich enough without wondering how Hitchens might feel about things once he gets there. If he gets there. For all the sadness of his passing, I can’t help but consider the wonderful possibility that I will be rushing to whatever the afterlife version of a library is to pick up Hitchens’ books about his surprise at finding himself there, and who all the bores are in Heaven, or wherever.

I strongly recommend Hitchens’ latest book “Arguably,” as well as any other essays you can get your hands on, like this one that Trade Paperbacks featured a few months back. So long, Christopher Hitchens.

An excellent account of Hitch’s last days from his friend, the novelist Ian McEwan:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2011/dec/16/christopher-hitchens-appreciation-by-ian-mcewan

And a compilation of remembrances over at Andrew Sullivan’s Daily Dish:

http://andrewsullivan.thedailybeast.com/2011/12/the-dish-tribute-to-hitch.html

All worth a read.