![]()

Jane Franklin raised twelve children, as well as several grandchildren and great-grandchildren, in colonial America. She lived in poverty for most of her life, stitching bonnets and managing a boarding house to make ends meet. Her brother Benjamin was one of the most successful men of his generation, a printer, postmaster, essayist, inventor, newspaper publisher, writer of Poor Richard’s Almanac, the most famous scientist on the planet, signer of the Declaration of Independence, representative in France during the Revolutionary War, and a participant in the creation of the Constitution of the United States, among many other things. Although their two lives diverged dramatically, they each remained one of the other’s closest friends, or as Jill Lepore puts it in Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin, “He loved no one longer. She loved no one better.”

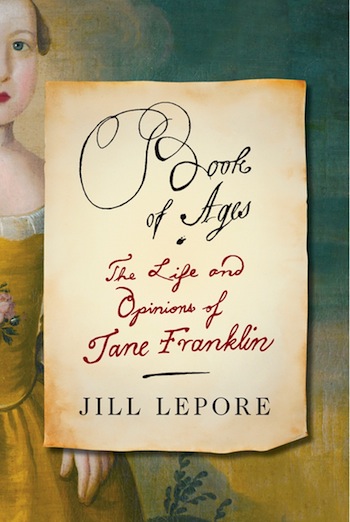

By the time I first learned that this book was being written I was already a big fan of Lepore’s (see, for example, her work in the New Yorker), and also already something of a Ben Franklin obsessive. It is a pleasure to report that Book of Ages is a strange and remarkable accomplishment. In less than 270 pages, Book of Ages does quadruple duty. (1) It tells the tale of Jane Franklin, her experiences through the American Revolution, and the views that she developed through her difficult, often tragic life. (2) It explores how Benjamin Franklin’s work was influenced by his lifelong relationship with his sister. (3) Even more, Book of Ages ends up being about the colonial world inhabited by people like Jane Franklin, common folk neither rich, nor famous, nor advantaged, nor fortunate. (4) More still, it is a book about history writing itself. Given how little remains of Jane Franklin’s correspondence, it is fascinating to watch Lepore weave together what does exist into a full narrative.

Jane and Benjamin Franklin were close even as children. Known as “Benny and Jenny,” she was the youngest of seven sisters, he the youngest of ten brothers. Much of Book of Ages showcases the contrasts that emerge between their lives. For instance, as a child Benjamin Franklin was taught to read and write, and he attributed his climb out of the working class to the latter of these skills. But Lepore notes that, as a woman of this era, Jane Franklin would only have been taught to read, not write. The limited writing skills she did acquire would have been taught to her by her brother.

At age seventeen, Benjamin Franklin ran away from their home in Boston, making his way for his historic fresh start in Philadelphia (an adventure he recounts compellingly in his Autobiography). The same option never existed for his sister. When Benjamin Franklin went on to father his illegitimate son William with an unknown mistress, this could have endangered his respectability. But, in what Lepore calls “an excellent bit of luck,” his ex-fiancé who had gone on to marry someone else suddenly became a widow. She moved in with Benjamin Franklin and raised William as her own. Jane Franklin’s own marriage drove her life in a very different direction.

At the age of fifteen, very young for that time, Jane Franklin married a saddle maker named Edward Mecom. As Lepore observes, “Marrying the man she did, when she did, determined the whole course of Jane Franklin’s life.” It was one of the worst things to ever happen to her. Mecom may have been a drunk, and he was forever under crushing debt. Two of their sons suffered from mental illness, a condition they may have inherited from their father. It’s hard to know the day to day character of their marriage, but Lepore reports that “Jane never once wrote anything about him expressing the least affection. She hardly wrote anything about him at all.” They lived together in poverty, moving into her father’s house, with Mecom most likely in and out of debtors’ prison. Lepore notes the parade of debt collectors visiting Jane Franklin’s home, searching in vain for her husband, leaving each time with pieces of furniture. “Edward Mecom was either a bad man or a mad man.” How did Jane Franklin end up with him in the first place, and why so young? Lepore offers an interesting speculation: perhaps she was pregnant and had no choice but to marry. If so, the pregnancy never resulted in a child. This possibility allows Lepore to draw another comparison between Jane Franklin and her brother, reflecting again the gender inequities of the colonial era. If her speculation is true, then Benjamin Franklin’s own child out of wedlock did not keep him from advancing in society as did his sister’s.

Part of the fascination of the early sections of Book of Ages is seeing how Lepore puts together Jane Franklin’s life with extremely limited historical resources. We have no letters written by Jane Franklin before the age of 45! Lepore wrings what she can from Benjamin Franklin’s existing letters to his sister, what we know of his own life in Boston, what we know of women’s lives generally from that time, and other historical evidence, such as debt records. We also have what Jane Franklin herself later wrote about those times. Lepore occasionally quotes Jane Franklin’s later letters during the early part of the biography, sometimes quite out of context, simply to “allow the reader to enjoy Jane’s company.” There is another resource: a little hand-sewn booklet that Jane Franklin bound and wrote, which lists the birth and death dates of members of her family, which she entitled “Book of Ages.” Lepore describes the experience of holding it in her hands as, “so small, so fragile, so plain, her handwriting so tiny and cramped.” Along with quotes from Poor Richard’s Almanac, Lepore uses entries from Jane Franklin’s “Book of Ages” throughout the biography as a kind of framing device.

Lepore also takes every opportunity to extend the account with long asides about what life was like for people like Jane Franklin and Edward Mecom. These asides guide us through topics such as women’s education, tuberculosis, and debtor’s prison. We also get a brief appearance by a figure I think we should all be talking more about: Patience Wright. Wright was America’s first famous sculptor, creating lifelike wax figures three decades before Madame Tussaud. Her brash and vulgar interactions with her subjects were notorious. She reportedly addressed the king and queen of England by their first names. Wright is even claimed to have spied for the colonies in the lead-up to the war, sending messages hidden in wax heads. But perhaps most striking was her sculpting style, a process that Angela Serratore describes in the Smithsonian: “Wax, to be molded, must be kept warm; Wright worked the material in her lap and under her skirts—and then revealed the fully formed heads and torsos as though they were being birthed.” Wright understandably provoked big reactions, and so she can serve as a kind of lens, magnifying attitudes of the time. Abigail Adams referred to Wright as “the queen of sluts.” Benjamin Franklin became one of Wright’s biggest supporters—and he learned of Wright in a letter of introduction written by his sister.

Lepore makes a strong case that Benjamin Franklin’s thinking was influenced by his relationship with his sister. Of all his many correspondents, he wrote to Jane Franklin the most. They bickered throughout their lives over religion, she maintaining that salvation can only be achieved through doctrinal faith, and he, belonging to no church, holding that piety should instead consist of doing good. Throughout the book Lepore argues that many of Benjamin Franklin’s works are directly informed by his connection to his sister, from Poor Richard’s Almanac, to his “Silence Dogood” letters, to his widely published (and today often willfully misunderstood) essay “The Way to Wealth,” the latter of which she claims he wrote in part as advice to one of his sister’s sons.

Lepore maintains that such a close relationship with a poor and common woman helped to keep Benjamin Franklin grounded. “She was, all his life, his anchor—and, in the end, his only anchor—to the past.” Even as his place in the world rose, Benjamin Franklin often wrote for and about the American working class, and his sister represented his enduring link to that world. Lepore notes that many of Poor Richard’s maxims, such as “One Half of the World does not know how the other Half lives,” ring true with this link. As the American ambassador in France during the war, Benjamin Franklin expertly milked his celebrity status as a wild frontier philosopher—an image he played up, for example, by wearing a coonskin cap, a fashion choice so celebrated that it inspired a ladies’ hairstyle trend called the “coiffure á la Franklin.” As part of this sly self-mythologizing he had his sister craft and ship him boxes of their family’s traditional homemade soap (their late father was a soap boiler by trade), which he would distribute as gifts.

In a tricky—but I think ultimately fair—maneuver, Lepore has it two ways at once with her biography of Jane Franklin. On the one hand, Jane Franklin is cast as an everywoman, a peek into the lives of the common folk of the era, and the hold by which her skyrocketing brother kept one foot in the common world. On the other hand, we see Jane Franklin grow into something else: a thoughtful citizen with an insatiable appetite for reading, and, increasingly, someone with opinions of her own.

Much of Jane Franklin’s life was bleak. Of her twelve children, she was outlived by only one. The last line in her “Book of Ages,” which cataloged that march of sorrowful deaths, is a quote from the Book of Job. Still, there is joy to be had in seeing her grow old and become increasingly well read. Her correspondence with her brother becomes warm and casual. We learn of her adventures fleeing Boston as it was occupied during the revolution. A supporter of the American cause, she reacts in utter disbelief to news that her brother’s son William, by then the Governor of New Jersey, remained a loyalist, an allegiance that caused a bitter break with his father. We see her read and accumulate her own collection of books, including any pieces of her brother’s voluminous output that she could get her hands on. We even see her reflect on her own fate, and consider its implications for politics and religion. She began to consider, for example, that her circumstances might not be simply the will of God, but the effects of earthly politics. We see that very late in life, through her brother’s assistance, she finally got a residence in which she had her own room.

Those interested in a straightforward biography of Jane Franklin will not find it in Book of Ages. But readers like me, whose interest in the founding of America has spilled over into a fascination with that very different—though not all that distant—world, will find much to love in Lepore’s story of the life of Jane Franklin.

- Robert Rosenberger is a philosophy professor at Georgia Tech. He studies the philosophy of technology, and some of his popular writing has appeared in Slate and the Atlantic.

Reblogged this on hellterskelter.