Read if you liked Office Space and The Things They Carried

Status:

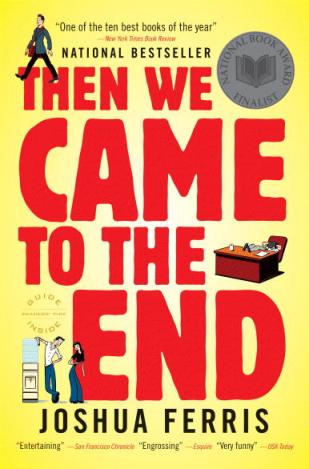

THERE IS A SENSE THAT ALL TOO MUCH HAS BEEN MADE OF JOSHUA FERRIS. In 2007, at the age of 23, he published his debut novel “Then We Came to the End,” which was kindly reviewed in the upper echelons of literary acceptance (i.e. lots of publications with ‘New York’ in their names), won the 2007 PEN/Hemingway Award and was named as a finalist for the National Book Award.

Those superlatives are things dreamed of by authors — good authors — three times Ferris’ age. They were viewed with skepticism by those of us who, in 2007, at the age of 27, had not published anything anywhere and could barely afford to buy any publications with ‘New York’ in the title because we had, like Ferris, dropped a bundle on an MFA in writing. On the other side of adulation, he was written off as the manufactured product of a publishing industry hungry for best-selling young phenoms, someone other writers loved to hate, an author for whom it was easy to say, with high-minded resentment, “I think all too much has been made of Joshua Ferris.”

As it turns out, yes, too much was made of “Then We Came to the End.” But that doesn’t mean it’s not worth a read. It is a good book, and an exceptional achievement for a 23 year-old. And while it seems clear that Ferris was graded on a curve, he still manages high marks. He’s like Spud Webb in a dunk contest: he may not seem like he should be there, but he sure can dunk, and eventually you really enjoy watching him win.

“Then We Came to the End” is a comic portrayal of a Chicago advertising agency, post-internet bubble, when layoffs were steady and ruthless. Setting anything in Corporate America is hazardous for any young writer, and it’s almost an achievement in itself that Ferris at 23 didn’t churn out another tiresome “What’s wrong with the world and why the world deserves it” story. He acknowledges and possibly excises the temptation with one of his characters, an aspiring novelist writing what he describes as a “small, angry book about work.” The only obvious misfire comes early, with a hallmark of insufferably pretentious prose: a Tom Waits reference where none belongs. Ferris’ office schlubs accept “walking Spanish,” a reference to a Waits song I’ve never heard, as their euphemism for heading to the meeting where they will be fired. It’s possible, but not at all probable, that they would be so sanguine or hip about something that, according to every other word in the book, has them completely terrified.

We were fractious and overpaid. Our mornings lacked promise. At least those of us who smoked had something to look forward to at ten-fifteen. Most of us liked most everyone, a few of us hated specific individuals, one or two people loved everyone and everything. Those who loved everyone were unanimously reviled. We loved free bagels in the morning.

Fortunately, the whole “walking Spanish” thing fades harmlessly into the story, as do a few other tricks Ferris pulls. You want to be annoyed with the over-clever use of the 1st-person plural, until you realize it’s pitch perfect for channeling the confusion and concerns of these expendable mid-level employees*. You may want to accuse Ferris of writing hollow characters, who in a couple of “ripped from the headline” incidents, could be a weak commentary on morbid sensationalism and cultural banality. But eventually you start to remember their names, and understand that you know these characters in the same strange way they know each other — and you are both moved and terrified by their actions. You may also want to accuse Ferris of ripping off David Foster Wallace, and then…well, that is probably fair. Although “Then We Came to the End” is far more contained and manageable than anything Wallace ever put on paper.

In the years before his explosive debut, Joshua Ferris worked at a Chicago advertising agency, post-internet bubble, when layoffs were steady and ruthless. It was a moment of upheaval, when older workers with years of wisdom and experience could be replaced by hungry youngsters who knew Photoshop and were willing to take less money for more valuable skills. The tech age didn’t just make the typewriter useless; it banished an entire segment of American workers into obsolescence, a tendency that was accelerated once the bubble burst and things got serious. “Then We Came to the End” is about a century that was ending for some people, and a century that was just beginning for others. As one of the beginners, Ferris can’t help having a perspective that watches while others amble towards their unhappy fate. Lucky for us, he also brings in respect, sympathy and a little bit of love.

Do you want to trade paperbacks?

—————

*The 1st-person plural is put to extraordinary use in Kate Walbert’s “Our Kind,” a book so good I can’t comment except to say: Read it now. Any time you spend on a review would be time you’re wasting by not reading “Our Kind.”