Alexander Hamilton and Washington: A Life by Ron Chernow

FOR PEOPLE LIKE ME, WHO ARE DEDICATED BUT DECIDEDLY AMATEUR READERS OF AMERICAN HISTORY, there are a lot of good options to choose from. If your tastes lean more toward ideas and cultural context than the personal stuff, you can look to authors like Gordon Wood, who bind together stories about the founders under themes like “character,” or explain how their Christianity or atheism, or that fact that the FF’s were gardeners or closeted homosexuals, or both, helped shape the course of human events.

If you’re really into ideas, you can turn to surly geniuses like Gary Wills, who can take a particular event or document — the Declaration of Independence or the Gettysburg Address, for example — and make riveting work out of tracing its intellectual roots in the Scottish enlightenment or thanatoptic poetry, respectively.

Howard Zinn has taken on the noble effort of showing how the actions of the Great Men who get the attention affected everyone else who was around at the time. “A People’s History of the United States of America” is something close to excellent, but should be read with the understanding that not every person who did anything of historical significance did it by way of a dark capitalist conspiracy. The right kind of reading in these books can provide an important awareness about how messy our path has been and likely will be, and get you primed for the nuances and complications of book like Reinhold Niebuhr’s “The Irony of American History.”

For the more narrative, orchestra-swelling angle, try Joseph Ellis or David McCullough. For the more narrative, stomach-churning stuff, you can check out those Drunk History videos online.

Then there are guys like Ron Chernow and biographies like “Alexander Hamilton” and “Washington: A Life.” The best description of Chernow’s approach might be ‘the granular,’ in that he documents each man’s life down to very smallest of details. It’s not so much narrative or thematic as it is simply observant. We learn about the backgrounds of Hamilton’s benefactors on the island of St. Croix where he was born, and are told that on his voyage to college in New York, the ship caught fire and “crew members scrambled down ropes to the sea and scooped up seawater in buckets, extinguishing the blaze with some difficulty.” Of Washington, Chernow spends time on his near-constant worry over the finances of Mt. Vernon, his chiding letters to his employees there and his deep concerns about the discretion of his dentist. But we also hear about Hamilton’s abolitionism and dedication to his family, and that Washington’s mother’s shrill disapproval may have set the mold for his commitment to duty above all, that over the years he took in various orphaned members of his family, and that his stoicism was critical to holding together a young country looking for just about any reason to tear itself apart.

One of the many reasons to read these books is the deep connection between the two men. As relationships between the founding fathers go, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams get most of the attention for their academic and adversarial exchanges about the genesis of the country, which they wrestled over as President and Vice President and in years of correspondence, before poetically dying within hours of each other on the 50th anniversary of declaring independence. The professional and personal interactions between Washington and Hamilton lacked such made-for-TV dramatics, but were in the end far more influential on the workaday construction of an enduring republic and the shape of the nation we know today.

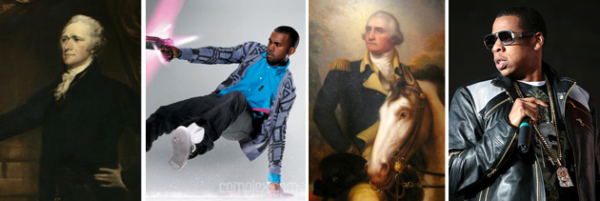

Washington’s importance is undeniable; what often goes unremarked, however, is that Hamilton was by Washington’s side for most of the Revolutionary War, the drafting and defending of the constitution, and the laying of foundations for America’s government and economy during Washington’s presidency. When a looming war with France threatened to pull Washington out of retirement, he insisted against the wishes of President Adams and the decorum of military succession on elevating Hamilton to his second in command. The two men were cornerstones of each other’s success, from the battlefield through the drafting of the Washington’s farewell address, and to praise one is to praise the other. An apt comparison might be between Kennedy and Ted Sorensen, although an odder but more illustrative parallel can be made to Jay-Z and Kanye West: the patriarch reaching the peak of his abilities, and shaping his entire career, through the volatile creative genius of his upstart protegé.

OF THE TWO, HAMILTON’S BIOGRAPHY IS THE MORE INTERESTING. Hamilton rose from less than obscurity, the illegitimate son of an insolvent debtor on St. Croix, and by his early 20s was one of Washington’s closest advisers. Those humble origins forged in him progressive attitudes about social and economic freedoms that might open the way for more people like himself. Hamilton can be maligned as the nation’s first enabler of Big Business excesses, but it’s important to remember — and Chernow is subtle but effective in reminding us — that the manufacturing and finance sectors he and Washington took pains to establish in the first years of the republic were the alternative to the aristocratic limitations of Jefferson’s agrarian South. The prowess that made Hamilton successful also made him combative, ambitious, less than prudent in his relationships with women, and eager to spar via the chosen method of the time — pseudonymously published essays — over almost any perceived slight, political or personal. These qualities would ultimately lead to his death in the duel with Aaron Burr, followed by lamentations for a man who had accomplished more before the age of fifty than most of his longer-lived contemporaries.

Comparatively, Washington is a constitutionally less exciting subject. The first president was not an enlightenment scholar or inventor like others of the founding generation, and was little known for intellectual achievements or innovation. Chernow focuses instead on an alternate strain of genius: Washington’s reservation and pragmatism, his unwavering sense of honor and duty, and finally, his willingness to relinquish power in the best interests of his nation. Washington’s precedent was his greatest achievement. Again and again throughout his life he acted with incredible understanding that his behavior would set the path for the future of his nation. He seems to have never lost sight of the words of his first inaugural address that “the preservation of the sacred fire of liberty, and the destiny of the Republican model of Government, are justly considered as deeply, perhaps as finally staked, on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.”

For all of their charms, a few items must be taken with a grain of salt in these books. The first are the portrayals of Adams and Jefferson. Adams rarely appears except in vain and hyperbolic criticism of Hamilton or Washington, and there is plenty of evidence to balance out the vision of him as a man who did little but sputter in resentment. Jefferson is almost entirely villainous in Chernow’s accounts, and comes across as a calculating and duplicitous man who took advantage of Washington’s faith in him to further his ideology over his country. Jefferson was in fact calculating and duplicitous, and secretly bankrolled vitriolic published attacks on Washington and Hamilton while serving as secretary of state. He was also often blinded by ideology, once saying of the appalling violence of the French Revolution, “rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam and Eve left in every country, and left free, it would be better than it is now.” But for all that, it’s worth noting that Jefferson and his followers had a distinctly different vision at the outset of the American experiment, one that remained grounded in its agrarian past and did not welcome urban centers, banking and the federal interests that Washington believed were necessary to hold states together into a functional union. Jefferson’s is not an altogether unappealing vision, despite the fact the he played to the lowest common denominator in asserting it, and competition for the soul of the nation was never fiercer than at its origins.

That raises another issue, which is the temptation to compare the era of politics Chernow writes about with today’s debates. It’s a difficult temptation to resist given that the adoptive rhetoric of today’s parties is so similar to what was used in those days. But when someone in the 1790s voiced their opposition to taxes and tyranny, it came from an experience of actual taxation without representation and subjection to an all-powerful central government. It’s a different issue altogether from someone today who puts on a tri-corner hat and begins calling for revolution because they are expected to fulfill a basic tenet of responsible citizenship. As I was reading I felt the impulse to post snarky Facebook comments about Washington’s support for carrying a public debt and his warnings about an aversion to paying taxes, but there is a difference between these sentiments when they are expressed in a nation with no precedent for public borrowing and a history of genuinely oppressive taxation, and a country with two centuries, more or less, of successful financing, and the lowest tax rates in decades. Neither side of the argument gains much by conflating the two. If there is anything to be learned from the example Washington set, it is the importance of resolving to act based on the circumstances before us; not to fight for the satisfying but temporary victory of argument, but for the lasting interests of the nation and its future.

And that is why we remember him as such a badass:

.

Do you want to trade paperbacks?

[…] our review of Chernow’s books on Hamilton and George Washington, we proposed that Hamilton was the Kanye to Washington’s Jay Z. Lin-Manuel Miranda, the […]

[…] This may be your best chance to show both your nerd cred and your cool cred by giving a doorstop historical biography that is also the basis of a hip-hop Broadway sensation. Read here if you need more convincing. […]

[…] Jay Z and Kanye West Share this:Like this:LikeBe the first to like this post. from → Other People's Stuff ← Inventory: The Broom of the System by David Foster Wallace No comments yet […]

[…] dick move has earned him condemnation in multiple volumes, while history has judged Washington far more generously than his own time. In his two terms, the […]

[…] faith that enables King Henry to have what he wants. (N.B: This interpretation may have to do with my current reading on Alexander Hamilton, another impoverished, polymath upstart who found himself the closest adviser to the head of state […]