Yesterday the United States Geological Survey was busy gathering and reporting data about the 5.9 magnitude earthquake that rippled up the east coast in the late afternoon. With all the quake news, it went generally unremarked that just hours before, the USGS had announced a 40-fold increase in the estimates of natural gas reserves available in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale. Those reserves would be extracted largely through hydraulic fracturing, or hydrofracking, in which liquid is injected underground to rupture rocks and release the trapped gas.

Yesterday the United States Geological Survey was busy gathering and reporting data about the 5.9 magnitude earthquake that rippled up the east coast in the late afternoon. With all the quake news, it went generally unremarked that just hours before, the USGS had announced a 40-fold increase in the estimates of natural gas reserves available in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale. Those reserves would be extracted largely through hydraulic fracturing, or hydrofracking, in which liquid is injected underground to rupture rocks and release the trapped gas.

Given the overlap of these two events, it seemed appropriate to re-post the piece below.

—————

March 23, 2011

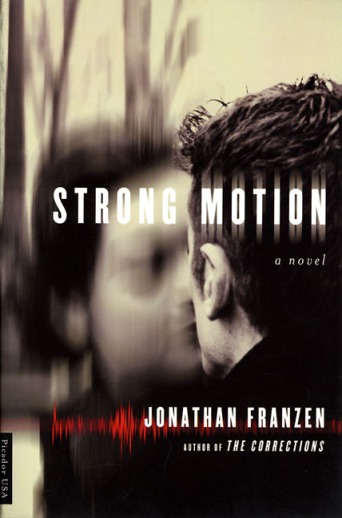

Strong Motion by Jonathan Franzen

Franzen demonstrates why he is always mentioned alongside David Foster Wallace

Status: Available Reserved

WITH ALL THE TERRIBLE EARTHQUAKE NEWS OUT OF JAPAN, no one can be blamed for missing another earthquake story a little closer to home. In the last six months, the state of Arkansas has experienced something on the order of 1,000 small quakes, mostly under 4.0 in magnitude, but one — a 4.7 — that was the strongest quake in the state in 35 years. The drastic up-tick in seismic activity is being linked, by experts and amateurs alike, to the increased use of high-pressure injection wells, underground spaces where companies in the natural gas business store wastewater. In other words, pumping a bunch of polluted water underground is the suspected cause of a rash of recent earthquakes.

This is roughly the backdrop of Jonathan Franzen’s book “Strong Motion,” his second novel and, in the era-tracking trend of “The Corrections” and “Freedom,” his end-of-the-1980s-early-1990s book. The domesticity and accessibility of Franzen’s most recent works, “Freedom” and the essay collection “The Discomfort Zone,” make it easy to rate him as a really great writer, but perhaps not a genius. “Strong Motion” is not only very different from its successors, but also evidence of what the author is capable of, starting with the ability to foresee a corporate and geological catastrophe 20 years ahead of time. More than any of his other novels, this one explains why Franzen was once called an heir to Pynchon and a contemporary of David Foster Wallace, for it is a morose, research-heavy, science-inflected, experimental and often overwritten critique of so much of what people endured at the dawn of the “information age.” All that and a climax straight out of DeLillo’s “White Noise.”

This is roughly the backdrop of Jonathan Franzen’s book “Strong Motion,” his second novel and, in the era-tracking trend of “The Corrections” and “Freedom,” his end-of-the-1980s-early-1990s book. The domesticity and accessibility of Franzen’s most recent works, “Freedom” and the essay collection “The Discomfort Zone,” make it easy to rate him as a really great writer, but perhaps not a genius. “Strong Motion” is not only very different from its successors, but also evidence of what the author is capable of, starting with the ability to foresee a corporate and geological catastrophe 20 years ahead of time. More than any of his other novels, this one explains why Franzen was once called an heir to Pynchon and a contemporary of David Foster Wallace, for it is a morose, research-heavy, science-inflected, experimental and often overwritten critique of so much of what people endured at the dawn of the “information age.” All that and a climax straight out of DeLillo’s “White Noise.”

Yet, the story also has a lot of heart. The earthquakes are, as I mentioned, the backdrop. They are the scenery in front of which Franzen’s characters, exert pressure, collide, move and crush each other. “Strong Motion” is set in the metro-Boston suburbs, and rather than some form of Big Energy, the earthquake-causing corporation is a chemical and arms conglomerate. Most of the action follows an over-smart and under-happy young man who often seems like he should be named Schmonathan Schmanzen, but is instead named Louis Holland. As a result of the quakes, Louis meets a woman;.she appears to be indifferent and vaguely put off by him until they’re suddenly in bed, planning to move in together and working to uncover the source of the so-far mild quakes. That’s just the beginning of a plot that involves a cultish pro-life group, old lovers, a new age grandma, an unhappy mother with millions of dollars, a pot head father and a manipulative sister with a hamster named Milton Friedman.

It’s hard, from this vantage on Franzen’s fiction, not to read the characters as archetypes of a certain time. Franzen is now famous for capturing spectrums of American life in his big, best-selling books; as Time magazine wrote, he is “a devotee of the wide shot, the all-embracing, way-we-live-now novel.” With that in mind, there is a decidedly gen-X feel to “Strong Motion,” with its post-Reagan unhappiness, its smugness and its preemptive concern over the digitalization of our lives. Or perhaps it’s just the description of “advanced” computers that take hours to run programs that puts me in the mind of a period piece. But as the book progresses Franzen manages to break his archetypes out of their categories, revealing recognizable, if not fully-formed, human beings and getting at what a “social critique” is really supposed to be.

There are plenty of reminders that “Strong Motion” was written by a very young writer. At times, his characters’ unhappiness is relentless, and manifests itself in gloomy, grad-school devices, like describing cars as designer shoes, siding with sidewalk litter as the city’s natural fauna, and a long debate, complete with lines of code, between the author and a computer named “the system.” Other, more reined-in efforts work better, though, for instance his spot-on description of “the smell of infrastructure” in Boston, and what is certain to be the longest and most genuinely moving scene written from the point of view of an urban raccoon.

“Strong Motion” is an ambitious book, and pays for it with occasional inconsistency. But for the most part, Franzen gets it right, dealing in rich detail with seismology, industrial production, digital systems, feminism, faith, reproductive politics, sibling rivalry, environmentalism, sex and love. He also gets extra credit for mentioning the Bread & Circus/Whole Foods where I used to work as a stock boy. In the final pages, Franzen takes another brave step for a young, striving novelist by giving his book a proper ending instead of just a cryptic cut-off point, and it is fun to watch him struggle between his cold-postmodernism and warm earnestness as everything comes to a close.

You’re first on the list. It’s what you might call ‘gently used’ just FYI.

No comment on what you’re doing to Karl’s Freedom.

I’m burning through Karl’s copy of “Freedom” and would like to get my name on the list for Strong Motion,” please!