The back cover and the first page of Sophia Shalmiyev’s Mother Winter explain that Russian sentences begin backward—so to understand Shalmiyev today, we must start at the beginning. The book describes 1980s Leningrad, anti-Semitism, her mother’s abandonment, and her emigration to America with her father. She writes about the early Riot Grrrl days, becoming a mother, and becoming an artist. Shalmiyev’s writing is brutal and lyrical— I kept stopping, awestruck, to absorb what I had just read. We caught up over email for this interview.

Let me start by saying this line of yours, from page 237, perfectly describes being a mother and writer: “This is the perfect exclamation of what it’s like to be a mother trying to write holding one thing inside all gushy warm and the other thing failing to come out against all odds.” I read that, underlined it twice, starred it, and put a bunch of exclamation points next to it. Because yes.

I am glad that the very corporeal and seemingly indecent line appealed to you. It may not grab everyone for the very reason it was poignant for you. Erasure often occurs when a thing is gory and profound but doesn’t belong with how we wish to see ourselves, or when looking at others, mothers especially, is too gross and takes away from the comforts of our benign narcissism.

That is my actual experience as a person with strings of empty cans loudly dragging around behind me like a car announcing a celebration: Mother. The children in my head and the children in my life are louder than my thoughts and ideas for the most part. When I do get that god-like quiet behind my eyes and begin to type, paint, sketch, take notes, it is still a major tick-tock race back to them. Always back to them. Until they are gone, and I realize that this structure and this container that frustrated me also got me through the waves of a writing life. It’s like keeping in a tampon while taking a shit as quickly as possible and getting yelled at by a tiny needy person to come help her. Unless you are writing an “edgy” novel, or a poem where anything is fair game because no one is buying, most nonfiction isn’t allowed to be so real. And I am using the word “real” here ironically to slap my own hand from the cookie jar of possible clichés, because it is a loaded one, the way the word “natural” is full of holes that make us wince. The point is that you can’t use poetic, pedestrian, crass, bodily, street language in memoir, unless you get a pass somehow. I slipped this through the cracks, mainly by asking my editor from the start of the revision process to let me write about my female body with more candor and anger than I was used to seeing on the page. Zack Knoll is a rare bird and knows deeply what marginalized representations on the page can look like. I did set the reader up in the first few pages to let her know I am going for vaginal discourse, for my mother and for my daughter, and that there will be no epiphany, we will swim in our collective blood, shit, urine, discharge, whathaveyou, together. I do hope men also read that line and think: I am lazy compared to any woman out there and I should do more. Or, as I believe, most straight dudes should quit the arts game and start a day care center TODAY. Do art as a hobby or a side job the way mothers were and are forced to, yesterday, today and tomorrow, it seems. Thank you, Eileen Myles, for saying it in the NYT.

What was your process for this book? The form is interesting—at times, it feels like intimate journal entries; other times, stream-of-consciousness; and yet other times, you’re addressing your mother directly. Did you consciously choose your form(s) or did you let the book decide?

I don’t really know what a journal entry is compared to what belongs in a finished and published book. I do not journal. Kerouac was alright at journaling though, as were a few other men we call Great writers. It is supposed to be a recording, unvarnished and unedited, which isn’t in this heavily edited book. I get that the implication of journaling privately vs. publically is to move through your feelings, look at them later for perspective, at a distance, and learn something about yourself, then maybe condense that into your behavior to better your relationships and advance in life. If the writing is hot, heavy, bruised, brutal, and quick-tempered and it comes from a feminized body, we place it in a category much sadder than what we allow men to express. Maybe because it is just too close to the bone. Maybe this is my version of an action flick, of a buddy movie, of a chase scene, of montage. But as I say a lot: I am a character in this book. So is the mother I hardly know. So is my father and so is Luda. They are all written based on my memories and information and I play with throughout the text, in the form, in the scaffolding, which is how the book is constructed. Mother Winter is about exile and obsessions. Claire Dederer calls it a “motherless geography.” In order to slap it out of the hand holding tightly onto interiority, I must also build outward in the second person and sing it as though I am channeling the Bulgarian Celestial Choir.

What have you done to maintain a space for yourself and your work (writing and otherwise) within motherhood?

I left my husband over four years ago. I was still in love with him when I asked him to move out and I will probably continue to love him from far away (a fifteen-minute walk in Portland). I didn’t do this to maintain my writing space, but the thing you are not allowed to say is that no man is a practicing feminist when it inconveniences him. Also, our modern man doesn’t know how to pay a bill on time, research a pre-school, apply to it, get the scholarships there, acquire health insurance, make dental appointments, anticipate needs, find a good therapist, discuss uncomfortable feelings, plan a calendar of any sort… I can go on. Their independence is a farce. They are subsidized by women—emotional labor, domestic labor, and for many in my life, financially, as well. They may have this knowledge, magically, when they go to do paid work, but when it comes to unpaid domestic labor and romance, they suddenly get more disorganized and distracted than ever. I buckled under the weight of being the matriarchal force who was not just taken for granted but was received as hostile and mean for not loving to repeat myself over and over and get no new results. The muscles around my spine went out after my second kid and I started to walk my life back to when I wasn’t taking care of a man and his fragile ego and could only find pockets of solitude bracketed by nurturing: asking questions, teaching basic concepts and being patient with boys and men until I blew up, until they shrugged, and I collapsed. The men can deny it, but if I am not speaking about you or to you then please do go on being the present and responsible partner that you are. I still struggle around this due to basic circumstances of the straight woman—our choices suck. My pal Melissa Febos says she thanks her lucky stars she doesn’t date men every single day. She is not wrong to be grateful for her queerness. Men have either not figured out how to seduce women without the rape model or are so lazy, afraid, and anxious that they make us do all the amorous work, too.

My time can be arranged differently since my ex and I, rightfully, split the parenting time with our two children in half.

On page 32, you say “I could buy the ticket, take the ride, but never arrive at my body, clean and fed. Not until I cleaned and fed children of my own.” Do you think we need to become mothers ourselves before we can start to understand our own mothers, on some fundamental level?

Not at all. I love her fiercely, but I do not understand my mother, and I have been one for over a decade now. I kind of had an over-abundance of empathy for my dad and stepmom and I think that snaked away my porthole to a protected selfhood. They are both so mercurial and gorgeous and strange and needy and I got them on every level, so having patience for them didn’t leave much for me to explore. Always a caretaker. I think what we need to cultivate in order to understand mothers is a domestic revolt. An actual revolution. I think that we won’t care about mothers until the men do that work and do it for generations. The men will decide that raising humans is a job once they all do it full-time, read the research about raising kids (Mahler, Klein, Winnicott, Erickson, Anna Freud, Maslow) the way they seem to want to absorb Steinbeck or Saunders or philosophy. They can form bonds over this knowledge and take it off our plates so that we are no longer the cold fish with no maternal instincts, or the hair-on-fire shrew with twelve arms to hold everyone. It is all on the masculine culture to shift. Stop asking feminine people to do more housework. And by the way, the scope of “housework” has expanded, not shrunk, with the advent of technology. Then we can think of mothers as humans. No one will ever like or understand a victim. That’s mother. A good mother is a good victim.

I really loved how you’d intersperse these memories about Riot Grrrl. As a fellow woman of a certain age, I remember those emerging days of the movement—connecting with others overs zines, music, writing on our bodies. Now that many Riot Grrrls are parents, do you think this can help change the landscape of traditional stereotypes of motherhood? Do you see things changing with how society or women view the institution of motherhood? (Loaded question, I know.)

No, I don’t. To add to the above, I believe that our culture is completely fragmented by capitalism while counterculture is eating its own head in the comments box. I feel extreme pessimism about stereotypes changing for mothers, because there will continue to be poor mothers. I think that even someone like Maggie Nelson, whom people idealize and revere and hold up as an antidote to boring old tropes of a mother-writer (and who describes only the very best and most tender aspects of her own later-in life parenting in her last book) might come out and write that it is way harder for whoever takes on the woman-role in the family. Which is Silvia Frederici’s point: It is still a misogynistic system and a structure present even in queer and trans relationships—the woman-role, the womb-role, the lower-caste role, still exists and gets played out. But that allows me to feel hope in return. If I can admit to how terrible things are then I have the power to address the solutions fit for the named problem. Friedan, a rich lady, knew that we needed to give it a name to yell at and study. The truth is that only well-off women with children are ever ok, or they would have the chance to be so if they tried half as hard as an actual bohemian or working-class—or the disappearing middle-class—woman. They are called the idle rich for a reason, like a running car idling outside a school, poisoning our air until we must go home with a terminal headache.

My entry into punk rock culture was very naïve and didn’t feel like a rebellion because we were on food stamps and I worked at Burger King, a catering hall, and I tutored and babysat. I shared this money with my family. My parents wanted me to be a respectable kind of girl who had a part-time job at an office or any white-collar space, then hung around with idiots whose parents could get them into an elite college. I was to align myself with power, casually, as though that is ever a possibility for a poor immigrant girl. That kind of casualness available to the wealthy is what disgusts me and scares me about those who enter the counterculture and are “slumming it.” They can and do codeswitch and blend without repercussions. They have every advantage of safety nets braided of and by their servants’ hair, and I am to go sell my body for food and state school tuition and then chill and pretend we have a kinship because we like the same bands, or both think that dressing as sexy objects really sucks. I think they should make themselves known instead of lurking and loitering; they should start throwing their money into a pot to give to mothers who are selling their bodies to survive. Then we can all have an honest talk about feminism and motherhood. Those with a lot to say on the subject are silenced, traumatized, and have zero time. Time is money and money is hoarded or used as bribes to shut us all up. You couldn’t pay me enough to hang out with inherited wealth jocks.

You mention that “the art means we are going to do much more than survive the journey ahead.” How has art helped you survive, and thrive, throughout your life?

It may be no accident that each of these questions precedes the answer to some degree. I don’t have a formed thought about how art has helped me survive, exactly. Painting and writing have always been important, but I have rarely done it for mass consumption or with an idea of a career until fairly recently. That is definitely part of the sexist construct I was fed around the scarcity model for women, with a storyline about those who make it as hungry art monsters stepping over others or sad drunk losers who die early or are sensationalized. Having access to feminist art has been absolutely everything to me. After decades of being a professional underachiever, I told myself that there is a chain, a conversation, an anti-canon, a feminine life externalized that I want to be tied to for that exact reason: it is all about access, camaraderie and mentorship.

The passage you quoted is layered. My father, who weighed our suitcases to the ounce and still had our valuables confiscated at the airport for being over the limit, built crates and paid with borrowed cash to ship the art he collected in the Soviet Union to our future destination. He made many bad and extravagant decisions escaping our homeland and he knew this, but because he grew up so very poor and the idea that he could ever become an art collector of any sort was so ridiculous, he was willing to do dumb shit to stage this possibility. A woman from a family of scholars, of Jewish intelligentsia, whom he briefly dated, way above his station, was the inspiration for this strange and courageous ambition. The dog we brought was also like a drag show, right? We are either so secure and capable that bringing a fancy dog along to emigrate is no big deal, or we wish to simulate this destiny and act as if we will be, someday. Like buying good wine to go with stale bread as your paycheck runs out. Art with a capital “A” is still for the rich though isn’t it?

How do you think the creative community can support women, and mothers especially?

We need more grants and more spaces for parents. One concrete way is to offer childcare at every art and literary conference, or to pay women to cover their childcare at home if they are on your panel or are running an event. It is all pay-for-play at the core anyways, but even that has an extra fee attached to it if you are a mother. Why doesn’t AWP or the Portland Book Fest, or any other literary event have a budget line for childcare built-in, yesterday? There are science conferences galore that make sure there is adequate childcare. I am very disappointed in the answer AWP gives out about liabilities. This is a reality and there are ways to handle this with a lawyer and contract work. We need to leave empty chairs with names and photos of every parent who wanted to but could not come to a book fest and contribute their voice because of a lack of access to childcare. This is beyond basic and no one will even touch it. Storm the palace; have a walk out. Do something about this now. We can’t all just peddle our wares to the highest bidder, people.

What are you struggling with, as a parent and as a writer, right now?

I have many traumatized women and girls writing me to ask how to deal with having been raped and abused, how to become articulate and seen and heard, basically, an artist with a platform, despite feeling speechless and ignored. This is a struggle I am lucky enough to have because it means I am a safe harbor for someone out there, but one which I must point out, men will never be usurped by. I would love to see that dumbass who wrote about His Struggle, and made his wife crazy doing so, try to answer my inbox of raped women for one week and not be admitted to a psychiatric ward in a straightjacket. I would even visit him and write about it while he recovers. I, willingly and anxiously, spend many hours giving out resources, advice, suggestions and encouragement to women who are flooding and depleting their cortisol, burying them alive, so that they may live in their bodies without needing constant escape and eventually write about it and find community. Someone very close to me was recently raped and I am having a difficult time with that feeling of helplessness. It is an epidemic and we have no monuments and no memorials and no national holidays for all of us girls and women who have been brutalized and treated like objects then told we are liars. I want a Washington Monument where our names are etched in cursive on a long red wall. I bet it can extend to every single state and wrap the world. That is the only wall we desperately need right now.

What books inspire you, and what are you reading right now?

Conflict is Not Abuse by Sarah Schulman is what I am reading right now and so should everyone! All of her books have given me much levity and I have whiplash from nodding along. I talk in my book appearances about the choice to have so much white space on the page as a metaphor for multiple white sheets at a morgue. I have never done this for my mother. Never had that closure. Schulman writes this way, but in reverse. Her generation buried so much genius, so much magic, so much promise, so much fun, so much community, so much love and wisdom that cannot be replicated, and her record-keeping and eulogizing and writing over those white sheets is necessary. I learned so much about mourning and the responsibility of the living though her. I hope she sees this interview and glimpses her influence on this Brooklyn immigrant girl, by way of the early ’90s punk and club kid days, reading her writing about AIDS, about our cities, and about cultural slaughter. I watched it on the news and barely understood why and what, with only a few years of American speech in me, but I listened and danced and worshiped gay nightlife and grew up changed by it.

Anything by Eileen Myles, Renata Adler and Grace Paley, forever.

What advice would you give to a writer trying to juggle parenthood and writing?

Open your document any time you can; just look at it. Women—get selfish and sacrifice your romantic relationships if that person is not willing to support you and be your muse and housekeeper from time to time. Find other single parents and trade time. Write at any inconvenient moment an idea strikes you but more clipped, as notes. Know you will not be forgiven for being visibly and erratically busy and overwhelmed with your writing life, and you will not be forgiven for seeming like a vessel with nothing but the family and day job to tend to. As Myles said at our reading: We are all motherless. We can’t have a mother because she is a sleeve of all the generations of abuse before and is never going to be good enough or available enough for some and will be smothering and have not enough boundaries for others. And remember that the aftermath of writing the book is much worse than writing it, just like with birth. Enjoy every sentence even when it feels terminal.

What’s next on the horizon for you?

My art exhibit at Powell’s in Portland. It is sixteen paintings based on Mother Winter, some direct responses to scenes on the page and some as pre and post book ideas painted as a way of entering that story using a different language. It is up through AWP, which may be too late for when this comes out, but I hope to tour with it a bit so if someone wished to curate an art show about hybrid bodies of work and hybrid body representations, I would love to continue to show the work.

I am finally writing my next book, I Married the Butcher to Get to the Bone. It is hard to talk about a work-in progress, but I am fully in the womb with this one and it feels like home.

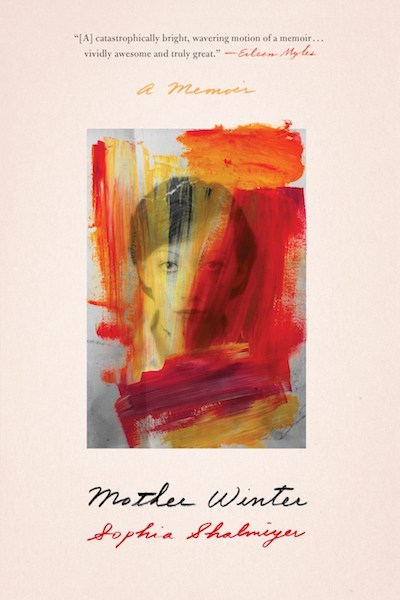

Photo credit: Thomas Teal.

“No one will ever like or understand a victim. That’s mother. A good mother is a good victim.” If Shalmiyev, or other women, really believe this, then why do women continue to posture as archetypal victims? Don’t they want to be liked and understood? To her and her ilk, I would say, she hasn’t met the right mothers. I was a single parent from 18-21, 23-25, and from 31-on to 72. What I learned is that ‘motherhood’ must change as the kids grow up. I was a great “new-mom” but a terrible mom when my kids were in elementary school, according to the motherly canon. I was better the older they got until now (they’re 53 & 48), I get their sincere thanks for being kind of mom they needed at the time. I learned my lines and knew my role at each stage, including the “tough love” when they were in their drug experimentation phase. I also learned that ‘liberated’ women were a pain in the butt. Affluent/white women could afford to pshaw traditional marriage & family, while most women I knew would have given their left tit for man who liked to work and felt he should stick around and support his family. When I see how happy my kids are in their traditional marriages (they and their spouses are all well-educated & conservative), none of us feel like victims. Especially not me! I have to MA degrees (I was un-victim enough to write 2 MA theses), and taught college-level classes in sociology & poli sci for 27 years. I write full time now, but interspersed my academic papers with newspaper articles, columns, and feature writing. And no, I didn’t have a husband/friends to support my writing. People write because they cannot do otherwise. there are no victims when it comes to writing. There’s only finding excuses.