Amy Kurzweil is a writer and cartoonist. Her cartoons, comics, and prose have appeared in The New Yorker, New Yorker Daily Shouts, The Believer, The Toast, Spiralbound and Longreads, among others. She is the author of the graphic memoir Flying Couch, about her Jewish identity, her Holocaust-survivor grandmother, and inherited trauma. For more information follow her on Instagram or support her on Patreon.

Amy is teaching a free Zoom Toon class this Sunday, October 11th, at 2pm PT/5pm EST. Register here to join!

EB: Have writing and drawing always been connected for you, or do you think of them separately?

AK: I think of writing and drawing as two separate languages, and it’s like I’m bilingual.

EB: I love that!

AK: But in my case, I have limitations in each language, so I use both in symphony. In this metaphor, writing is my “official” language. I was always more innately proficient in writing than drawing, and also more trained—I got an MFA in fiction writing—and drawing is maybe something like a mother tongue I never really “learned.” This metaphor is imperfect, but I’m inclined to think of languages this way because there are several mother tongues in my family that are inaccessible to me. My mother was born speaking languages she’s now lost; German, Yiddish, and Polish still inflect my grandmother’s English. This might explain why, as a writer of prose, I began to feel like I needed another language to express, in particular, the emotional currents in the story of my maternal family in my first book. The more I draw, the more proficient I become in the drawn language. But since I came to drawing later—I started more seriously only in my 20s—I really lacked fluency when drafting my first book. In some ways, that lack of fluency yielded interesting results, just as a person speaking their non-fluent language finds creative or unique ways around the gaps in their vocabulary. I’m trying not to lose what’s unique about my visual voice as my drawing “vocabulary” advances.

EB: So, when you’re “speaking” each of these languages, what is your creative process for writing vs. drawing? Are they similar or different? I studied Russian in college, and I know that often how you think is influenced by the structure of the language you are speaking or thinking in.

AK: To continue this language metaphor, there are many moments of translation between writing and drawing in my process, for longform or shortform graphic work. I almost always start with writing. For a single-panel cartoon, I start with a few words texted out in the notes app on my phone. For a chapter of a graphic memoir, I start with a script in a word document. Then, my favorite part of the process is translating my word draft into a draft of a comic page onto graph paper. I see which words from my script remain in dialogue and narrative, and I see many words transform into series of images. I can’t explain exactly what transforms and why, but it has something to do with rhythm.

EB: That’s so cool. Thank you for sharing that. Do you ever write “straight” prose anymore? Or are words and images always married now for you?

AK: I write prose less and less these days, but when I’m moved to write something in just prose, it’s usually because the story or message feels very voice-driven, and that voice just starts to pour out of my fingers. As a prose writer, I’m challenged because I get too enchanted with the sound of my sentences and then it’s hard to edit my work. I don’t feel precious about my sketched drawings. I literally cut up my drafts with scissors, paste and rearrange sections of drawings constantly, and it doesn’t cause me pain. I have more trouble editing my prose sentences because I get attached to their rhythm.

EB: So, you said your MFA was in fiction. How did you begin writing nonfiction?

AK: Not to dodge the question, but I don’t have a clear understanding of the narrative distinction between fiction and nonfiction.

EB: But this series is called Non-Fiction by Non-Men!

AK: I’ve always been interested in stories that are from and about memory, whether they are called “memoirs” or not. I remember learning in grad school that “creative nonfiction” and even “memoir” were relatively new terms, developed for reasons of marketing and publishing. Books I was most drawn to in grad school—for example Swann’s Way, The Emigrants, and The Lover, were books about real experience, but they weren’t labelled memoirs. I think what I’m saying is: I like books with authority over their subject matter. I want to learn about something that really did, or really could, happen. My understanding of how memory works suggests that “did happen” and “could happen” are not so far apart. Some authorial accounts are fictionalized, which is a choice a writer might make for protective reasons. I don’t know if I could have told you why I chose to be explicit about writing “nonfiction” with my first book, other than intuition, or emulating the graphic memoirs that inspired me like Maus and Persepolis, but now I understand this choice as a political one. Flying Couch, among other things, visualizes an oral history account from my grandmother of surviving the Holocaust. Since history is and can be contested, I felt the burden of testimony, which means I needed to be explicit about the “nonfiction” of my family’s experience.

EB: That makes a lot of sense. I sometimes feel like people can dismiss the content as novels as “too outlandish” to have actually happened, even if they are based on real experience. There is a lot of power in saying, “No, this really happened. This is a real story.”

AK: Comics are really interesting when it comes to nonfiction, because the comic plane is inherently a fantastical one. In my book, mythical figures pop out of thin air in some scenes, but this doesn’t make Flying Couch fantasy. Perhaps more than prose, comics allow for the unreal, because there’s an innate understanding that the language of comics is symbolic. A symbolic form can allow for visual metaphors and still tell a true story.

But I haven’t really answered your question! I think the answer to how I began nonfiction is the answer to how my first book came about.

EB: So how did your first book—the incredible graphic memoir Flying Couch—come about?

AK: When I was an undergraduate and I took a class called Literature of the Holocaust. It was uncanny to encounter, in an academic setting, a history that felt so personal to me, since the lives of my parents and my grandparents were transfigured and, in some ways, defined by the Holocaust. I felt a strong impulse to contribute something personal, so for my final project I drew a short comic about my grandmother and the death of her longtime boyfriend, who was sort of like a grandfather to me. He was also a survivor, with numbers on his arm, and never talked about his experiences. She was quite blasé about his death. This struck me, and I began reflecting on her character, our differences, and her hilarious and absurd habits. Then my mother gave me a transcription of the oral history interview she had done with a historian at the University of Michigan in the ’90s. In this document, my grandmother revealed, in fragmented and longwinded and painfully precise and poetic detail, everything that happened to her: the bombing of the Warsaw ghetto, her escape through the wall, the death of her family, her survival in disguise. Meanwhile, I was penning personal narratives for creative writing classes, reflecting on my own identity as a Jewish American, my relationship with my mother and my grandmother, my anxieties. These narratives started to braid together, and Flying Couch became my senior thesis, a documentation of my grandmother’s testimony woven together with stories from my life. I wanted to create a graphic book because of that expressive requisite I mentioned above, and because I was falling in love with graphic memoirs. I mentioned Maus and Persepolis, and this is also when I first read Fun Home, Blankets, Lynda Barry’s work and others. I thought drawing comics looked easy. (Hahahaha!)

EB: Hahaha, indeed—I am so impressed by cartoonists and graphic memoirists. I don’t know how you all do it. In terms of research, what did you have to do to dig deeper into your family’s history? Did you interview family members, consult archives, photographs…?

AK: The interview my grandmother did with the academic historian was part of the Voice/Vision Holocaust Survivor Oral History Archive, now available online through the University of Michigan, and it’s a wonderful contribution by Professor Sidney Bolkosky. You can hear all of the interviews’ original recordings, along with transcriptions, and portraits of survivors. My other research involved clarifying details with my mother, looking up facts: dates and maps and things like that, but only to help me understand any questions I had about my grandmother’s interview—that was my guiding document and my authority.

I’d also grown up hearing a lot of her stories in fragment. She has a habit—still has a habit! She’s 94—of launching unprompted into story. Sometimes the stories are dark; there are several that come up again and again. This slow trickle of history throughout my childhood likely accounts for my need to hear more, and why being given her whole interview was so transformative for me. The challenge was, again, one of translation: how could I order her story for a narrative, without losing her voice and her emphasis?

Because almost everything from my grandmother’s life pre-Holocaust was lost, whatever photographs my family has from “the old country” are few and rare. I grew up looking at these photographs, and knowing they were precious. I think I drew almost every photograph we have from my grandmother and mother’s life in Poland in Germany into my book. There isn’t much that survived.

EB: Wow. That’s so special then, that you got to preserve those photos in your book permanently. All the more reason for writing the book as nonfiction.

AK: I really love those photographs. Especially the ones of my mother.

EB: A lot of writers of memoir and personal nonfiction often struggle with the ethics around writing about other people. How did you handle that in regard to Flying Couch? Did you ask your family for permission before writing about them? Did you share drafts with them? Or did you just wait until the book was published and say, “Here you go!”?

AK: For me, this is less a question of ethics than one of relationships, and also of craft. I don’t know what the moral choice is with regard to testimony in storytelling, but I do know what maintains my family relationships and what satisfies my narrative ambition. My family is extremely close and quite invested in each other’s success, but also protective. So, it has always been understood that I should tell ambitious stories that feel personally meaningful to me, and it is also understood that I will share those stories with them first, and they have veto power. Given my family dynamic, I would never defy their veto power, but I did feel, with Flying Couch, that I was able to find creative solutions to any objections. And wherever I failed, those were failures of craft. I also discovered that many of my mother’s edits, for example, made my book better: more honest and more precise. Although my book challenged her, I think it also inspired her own reckoning with our family history; she wrote and presented on her experiences, in her own voice, several times, post publication. So I do believe my writing has contributed positively to her life in that way.

With my grandmother, she’s not a reader, so she couldn’t cosign every choice I made in telling her story. I wanted to balance every depiction of her that came from my perspective with her story, from her perspective, in her own words from her interview. Ultimately, that balance worked. Her attitude toward my book was one of unbridled enthusiasm. It helps that she is theatrical and loves the limelight. “I’m a hit,” she says.

EB: Ha! I love that.

AK: This has been miraculous. She is one of my hardest-working salesmen, hocking books to her neighbors and friends—and she very quickly makes strangers her friends.

EB: My grandmother is the same way, actually. Doesn’t quite get the whole writing thing, but has convinced her hairdresser and all of her doctors to buy my book when it comes out.

AK: I’ll get my Bubbe on the case for your book promotion when the time comes!Going back to the original question though, I think reasonable people are ultimately moved when you care enough about their experiences to immortalize them. What can hurt people, I’ve found, is lack of context, or superficial exploration. This is why sharing your work with family can deepen it. It’s an opportunity.

EB: I think that’s a great way of thinking about it.

AK: Of course, people aren’t always reasonable, and sometimes the opportunity to explore past pain is too overwhelming.

EB: Okay, also a good point.

AK: In the end, spirit and intention matter. Flying Couch does seek to validate and celebrate the women in my family—and that’s true of my next graphic memoir about my father’s side of the family—so these are projects they can get behind.

EB: In addition to your memoir, I love your one-panel comics. Every time you post one on Instagram it brings me such joy! Do you consider those a form of nonfiction as well?

AK: Thank you for being a follower! That’s a great question. I think of single panel comics like craft practice. Liana Fink told me once that cartoons are like “playing scales” for her longer work—I love that—and also like an exercise in ideas. There’s some idea I want to get at, something absurd about the social world I want to expose, and I’m turning around the elements of a cartoon—the tropes, the classic characters, the turns of phrase—and trying to get it to yield something, turning the dials, like a lock on a safe, to see if it’ll open. Does this sound like nonfiction? I don’t know. But to the extent that humor—if not haha-humor then that little ahh-eyeroll a good New Yorker cartoon inspires—exposes something real, then we could say a great single-panel cartoon is, at least, truth-revealing.

EB: Definitely. Writing and drawing can be a very solitary, isolating practice, but having fellow artists and writers can make all the different. Who do you turn to for support and advice while making art? Who makes up your creative community?

AK: My partner, especially since the pandemic, fields a lot of my neurotic artist spirals into despair. I’m lucky he is an even-keeled person, whose M.O., since he’s an academic philosopher, is to be curious about my ailments rather than critical or trying to solve my existential angst—the worst.

EB: Ugh, totally the worst!

AK: I’m just going to have a lot of aches and pains, physically and spiritually, from sitting with my own mind and doodles all day. You have to have a sense of humor about these things. I’m so very lucky to have a partner who agrees my fussing routine is good material for laughs.

I also do a lot of texting. I have a writer friend who I basically “live-text” my life too, and a group of friends from grad school who feel like family; when they publish something I really feel like some part of me did too. I’ve become close with my various editors—I deeply appreciate that the people who have authority over my work also feel like peers. Every cartoon I draw, I text to cartoonist friends for immediate validation. It’s wonderful! I’m very proud of and grateful for these communities. And still: the fussing continues.

EB: I totally get it. I think the fussing must help make for good art, right? That’s what I tell myself at least. So, out of all the “aches and pains,” what do you find most challenging about writing nonfiction? And what do you find most rewarding?

AK: The same thing challenges as rewards: that when you’ve stumbled upon the key to a chapter, a resonant conclusion, a missing piece of the story that makes the whole thing work, is also when something in your life, or the world, clicks into place, and you have to stop and have… a moment. It’s profound. Writing nonfiction is a way to watch your life make sense. Or it’s a way to make sense out of your life. When you’re writing about real ideas or experiences, the living, the witnessing, and the writing are so intertwined.

EB: Finally, what is a favorite passage of nonfiction by a fellow “non-man”?

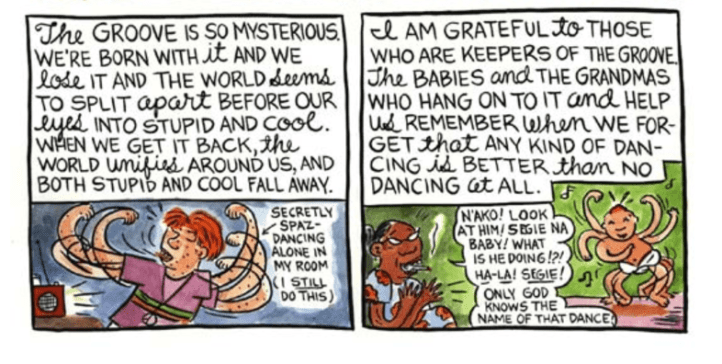

AK: I just love this whole book: Lynda Barry’s One! Hundred! Demons! Here are the last two panels of a chapter called “Dancing.” That drawing of a baby dancing just brings me so much joy. And I would like to remind myself, amid all this isolation and sitting still, that I need to get up and move.