by Michael Moats

JUMP TO THE LATEST ENTRY IN THE INFINITE JEST LIVEBLOG

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction to the Liveblog

Don’t Read the Foreword, pgs. xi — xvi

Hamlet Sightings, pgs 3-17

Wen, pg 4

Pot Head, pgs 17-27

One Who Excels at Conversing, pgs 27-31

The Entertainment, pgs 32-37

Keep Reading, pgs 37-42

Orin and Hal, pgs 42-55

Don Gately: An Introduction, pgs 55-63

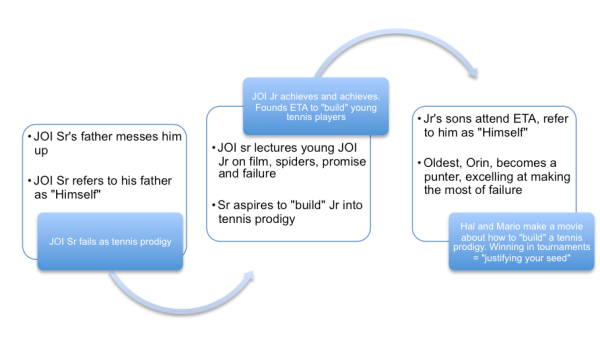

History of JOI and ETA, pgs 63-68

Two Addicts, an Attache and a German who Kicks it Altschule, pgs 68-87

Cloak and Dagger/Towels and Banter, pgs 87-127

Lyle and Friends, pgs 127-144

I Saw a Vision of Your Facetime, pgs 144-156

Justifying Your Seed, pgs 157-176

Anticonfluential?, pgs 176-193

Have a Cigar, pgs 193-219

An Aside, N/A

Too Much Fun, pgs 219-240

Waste Displacement, pgs 240-270

Analysis Paralysis, pgs 270-283

An Anticipated Retraction Regarding Dave Eggers or DO Read the Introduction

The Story of O, pgs 283-306

Double Binds, pgs 306-321/1004-1022

Eschaton!, pgs 321-342/1022-1025

Another Aside: DFW on Charlie Rose, N/A

White Flag, pgs 343-379/1025-1028

ONANism, pgs 380-418/1028-1031

The Pursuit of Happiness/The Clipperton Suite, pgs 418-434/1031-1032

8 NOVEMBER INTERDEPENDENCE DAY, N/A

This is Water, pgs 434-450

Visual Aid, N/A

Fire at Your Will, pgs 450-469/1032-1033

Somehow Relevant, N/A

Antitoi Entertainent [sic], pgs 469-508/1033-1034

Blue, pgs 508-530/1034-1036

Union of the Hideously and Improbably Deformed, pgs 530-538/1036-1037

Lenz Grinding, pgs 538-549/1037

Finding Drama, pgs 550-567/1037-1044

Getting Chewed by Something Huge and Tireless and Patient, pgs 567-619/1044-1045

The Phoneless Cord, pgs 620-638/1045-1046

The Darkness, pgs 638-662/1046

Brief Interview with Hyperhidrosis Man, pgs 663-665/1046-1052

Something is Rotten in the State of Enfield, pgs 666-682/1052.

Shallow Hal, pgs 682-716/1052-1054.

Cult Classics, pgs 716-735/1054-1062.

Every Unhappy Family…, pgs 736-755/1062.

Monsters, pgs 755-785/1062-1066.

Subsequent Events, pgs 785-808/1066-1076.

“….”, pgs 809-845/1076.

Images, N/A.

Alas, Poor Tony, pgs 845-864/1076-1077.

Tragedy Comedy, pgs 865-883/1077.

When it Hit, pgs 883-902/1077.

Using Your Head, pgs 902-911/1077.

Too Late, pgs 911-934/1077-1078.

Byzantine Pornography, pgs 934-958/1078-1079.

And But So Then?, pgs 958-981/1079.

.

What Happened? Pt. 1, pgs 3-1079

What Happened? Pt. 2, pgs 3-1079

—————

“INFINITE JEST” IS A BIG BOOK in so many more ways than just the one. Of the last few decades, it is the one piece of literature regarded as unimpeachably genius, a game changer, a generation-definer, an Urtext of whatever they’re calling fiction after post-modernism, an event, a whatever else you can think of. The almost universal response, whether you love or hate the book, is awe.

Awe at its length, awe at Wallace’s skill, awe at the pages and pages and pages of endnotes, awe that any single human brain — especially such a young one (Wallace was just 34 when the book was published) — could produce such a thing. What’s interesting is that these are only the outward impressions, the understanding of the book that you can get from just looking at it on the shelf, or flipping through the 388 endnotes, or biting off just one sentence, much less the entire book. What’s even more interesting is how these impressions branch and flower when you dive truly in.

Since Wallace’s suicide in 2008, the standard Kurt Cobain/Jimi Hendrix/Jeff Buckley Death of a Promising Young Artist dynamic has been at work, but magnified by the differences between the music and literature worlds. Where the former is constantly rewarding and celebrating the new and experimental, the latter tends to sniff with distrust around anything different. There is plenty of justification in the fear that technical experimentation or unrealism or fragmented narratives or other innovations are just bait to leave us with an indulgent, gimmicky, poorly structured piece of fiction snapped painfully around our wrists. Wallace managed to use experimentation and other weird stuff to get a genuine emotional response (though he may be held accountable for inspiring many terrible graduate writing workshop pieces that did not), and the fact that he had a certain rock star celebrity among American literature’s tweedy dweebs is not insignificant. His untimely and genuinely heart-wrenching death accelerated his stature to something a bit more messianic. Wallace has become a mythology, and because — now that we have “The Pale King” in hand — we know that he never wrote another work of the caliber and quality of “Infinite Jest,” the book itself orders his magnitude.

And so I repeat: it’s a big book. Which is why we’re trying something new here at Trade Paperbacks Fiction Advocate. Rather than spending the next month or two in hiding trying to read the 1k-plus-pages-plus-endnotes and then spending who knows how long trying to come up with some kind of coherent response, I’m just going to post as I go along. A live blog, or as close to live as I can get. So strap in, check back often, and read along if you like — and don’t hesitate to add your thoughts in the comments.

Finally, cross your fingers and hope that this won’t be as challenging as actually getting through the novel itself.

![]() August 1, 2012. What Happened? Pt. 1, pgs 3-1079. It’s been a little over three months since the last post of the Infinite Jest liveblog, and I recently noticed the first tiny urges to jump back in and read the book again. I’m not quite ready for all that, but it seems like the right time to tackle some of the most difficult questions lingering at the end of the novel: What the hell just happened? And why did it happen that way? (I’ll tackle the latter in a second post).

August 1, 2012. What Happened? Pt. 1, pgs 3-1079. It’s been a little over three months since the last post of the Infinite Jest liveblog, and I recently noticed the first tiny urges to jump back in and read the book again. I’m not quite ready for all that, but it seems like the right time to tackle some of the most difficult questions lingering at the end of the novel: What the hell just happened? And why did it happen that way? (I’ll tackle the latter in a second post).

If your experience finishing Infinite Jest mirrors mine, then after you threw the book across the room, picked it up and re-read the first chapter, then threw the book again, you went to Google and entered: “WHAT HAPPENED IN INFINITE JEST?”

This approach leads to some good resources for piecing together the actual events. Aaron Swartz at Raw Thought has the best explanation I’ve seen so far, a concise, linear and well-built case for what happened, even if some of his conclusions are debatable. Ezra Klein has some interesting thoughts about the impact, if not the actual details, of IJ’s ending in a post called “Infinite Jest as Infinite Jest.” And Dan Schmidt’s “Notes on Infinite Jest” answers some questions while raising others.

I’ll be using these sources — without which I would not have grasped what happened — to walk through things in detail here. But first, let’s establish that there actually is something happening at the end of Infinite Jest. The abrupt closing is easily written off as arbitrary or too clever, an easy way out of a monstrous narrative that offered no satisfying path to the finish line. But Wallace appears to have had an arc — or a circle — in mind, and filling in the blanks does not disappoint. Swartz quotes Wallace saying in 1996:

There is an ending as far as I’m concerned. Certain kinds of parallel lines are supposed to start converging in such a way that an “end” can be projected by the reader somewhere beyond the right frame. If no such convergence or projection occurred to you, then the book’s failed for you.

And in a 1997 interview with the Boston Phoenix, Wallace said:

Plot wise, the book doesn’t come to a resolution. But if the readers perceive it as me giving them the finger, then I haven’t done my job. On the surface it might seem like it just stops. But it’s supposed to stop and then kind of hum and project. Musically and emotionally, it’s a pitch that seemed right.

The ending’s meaning and intent are debatable, which is one of the great things about the book, but we should agree that there are both meaning and intent — and that the first step in deciphering them is an inventory of the main players as of pages 981 and 1079.

DON GATELY — The book ends with Don Gately on a beach after a massively unpleasant experience with his old crew and some Dilaudids. This is not the moment when Gately decides to get into recovery and head to Ennet House, but the image of him emerging from the warm, liquid womb of the drugs onto a cold beach with the tide way out is a strong, and significant, suggestion of a harsh “rebirth.” If this isn’t rock bottom, it’s hard to imagine any experience tough enough to chip down to lower level of shittiness than watching your friend get his eyes sewn open while you lay in a puddle of piss and M&M dye listening to Linda McCartney vocal tracks. I think the Linda McCartney part might be enough for me to seek help.

Of course, Gately is actually in his hospital bed dreaming of all this. He has been receiving visits from Joelle van Dyne, assorted Ennet House residents, and the JOI wraith as he recovers from a gunshot wound without the help of any addictive painkillers. I have wondered (but found no firm supporting evidence) whether Gately was given painkillers in the hospital against his uncommunicative will. On the one hand, it would explain why he dreams of taking massive doses of substances. On the other hand, if reintroducing Dilaudid into his system sends him straight back to memories of his rock bottom, let’s hope it means he won’t be getting back on the horse when he wakes up.

Gately has a hospital room vision on page 934:

He dreams he’s with a very sad kid and they’re in a graveyard digging some dead guy’s head up and it’s really important, like Continental-Emergency important, and Gately’s the best digger but he’s wicked hungry, like irresistibly hungry, and he’s eating with both hands out of huge economy-size bags of corporate snacks so he can’t really dig, while it gets later and later and the sad kid is trying to scream at Gately that the important thing was buried in the guy’s head and to divert the Continental Emergency to start digging the guy’s head up before it’s too late, but the kid moves his mouth but nothing comes out, and Joelle van D. appears … while the sad kid holds something terrible up by the hair and makes the face of somebody shouting in panic: Too Late.

Which echoes Hal’s memory from the first chapter:

I think of John N.R. Wayne, who would have won this year’s WhataBurger, standing watch in a mask as Donald Gately and I dig up my father’s head. There’s very little doubt that Wayne would have won.

JOHN “NO RELATION” WAYNE — We can confidently assume that John Wayne was an AFR plant at the Enfield Tennis Academy, along with Poutrincourt and possibly Avril Incandenza. He was last seen to have lost his composure after accidentally ingesting Pemulis’s Tenuate.

In Hal’s memory from the first chapter, Wayne is “standing watch” for them, and is then not able to play in the WhataBurger tournament.

JOELLE VAN DYNE aka MADAME PSYCHOSIS aka PGOAT — Joelle van Dyne is scooped up by Hugh “Helen” Steeply and questioned about The Entertainment.

HAL INCANDENZA — We know that Hal Incandenza is bound for his ill-fated college interview in the first chapter, but the last we see of him in the book (before Wallace meanders off to tell us all about Barry Loach) he’s acting weird in the pre-match locker room. Prior to this, Hal was wandering around the Enfield hallways in the early morning of the snowstorm. This is, notably, the last we hear from Hal in the first person, and he is just beginning to have trouble communicating. He’s showing the earliest symptoms of his condition in the first chapter.

Theories vary on what’s happened to Hal, but everyone seems to generally agree that he is feeling the effects of DMZ, the drug that caused a dosed convict to belt out Ethel Merman tunes every time he tried to speak. Hal too is losing control of what he is saying, but his manifestations are much less melodic.

One theory goes that Hal has synthesized the DMZ in his own body, a combination of the mold-eating incident from his childhood, the marijuana withdrawl, and possibly a significant intake of sugar on Interdependence Day that fed the DMZ still in his digestive system. The best explanation of this theory is the aforementioned Dan Schmidt’s “Notes on Infinite Jest.”

Another theory goes that Hal has been dosed with DMZ by the toothbrush. There have been prior incidents at ETA of toothbrush-as-vector for drugging, which Hal mentions in his last first-person sections. The toothbrush theory splits into two additional possibilities: One, that Pemulis did it out of anger at being expelled; or two, that JOI’s wraith did it. I think clues point to the wraith — because Pemulis’s stash is missing when he goes to retrieve it, and because Hal has not left his toothbrush unattended. It’s clear by now that JOI’s wraith is responsible for moving items around ETA, and for helping Ortho Stice in his match against Hal. It’s possible the wraith also left the bathroom window open on Hal’s hall.

Swartz at Raw Thought has some interesting speculations on why he thinks it was JOI-wraith, speculations that are linked to the origins of DMZ and the ultimate outcome of the novel — but these are the conclusions I was talking about when I said that some of them are debatable.

Based on the first chapter, we can also assume that most things get back to “normal” for the Incandenza’s by the Year of Glad. There is no mention of Hal’s mother disappearing, his brother dying or anything about Mario offered up as excuses for Hal’s questionable academic performance. It seems like there would have been if anything had happened.

MICHAEL PEMULIS — Whereabouts unknown, presumably not at ETA. Last seen searching for his missing stash of high-powered drugs and trying to talk to Hal about something important. Pemulis is currently living out his greatest fear of being expelled from ETA and going back to Allston. His behavior at this point is, therefore, presumed to be erratic and is possibly but, as discussed above, not likely to be linked to Hal’s developing issues.

ORIN INCANDENZA — After being seduced by Luria P(erec) aka the “Swiss hand-model,” Orin is undergoing a technical interview at the hands of Luria and the AFR leader M. Fortier. Orin is believed to be the holder of a master copy of The Entertainment, since reproductions have appeared in regions where he lived and places where his father’s enemies are, for example the Near Eastern Medical Attache in Boston and the Berkeley film critics. Orin breaks under the 1984-style interrogation, crying out “Do it to her! Do it to her!” Who this “her!” is is a subject of speculation, and had led some to assume that Avril Incandenza is present, and possibly is the same person as Luria P. This theory is sick and gross, but interesting.

It seems like Orin is still alive in the first chapter, since Hal mentions him without alluding to any kind of loss.

AVRIL INCANDENZA — Whereabouts unknown. Suspected agent of AFR, known enemy of Michael Pemulis and confirmed “ally” of John Wayne. It’s speculated though unlikely that she is also AFR agent and OUS-infiltrator Luria P., who hails from the same region of Quebec. Honestly, Avril’s behavior seems too genuinely neurotic for her to be functioning with alter-egos, and it doesn’t really add much to the story to clear up whether she is or isn’t Luria P.

LES ASSASSINS DES FAUTEUILS ROLLENTS (AFR) — Have captured Orin and infiltrated Enfield.

ORTHO “THE DARKNESS” STICE — Most of Ortho Stice had been forcibly removed from his post at the window, though some face remained, according to reports.

In the first chapter, he is set to possibly play Hal in the WhataBurger finals in the first chapter. One of Swartz’s debatable conclusions is that Stice is possessed by JOI’s wraith, which is thus prepared to “interact” with Hal through the match at the WhataBurger.

THE ENTERTAINMENT MASTER COPY — In the hands of AFR after either being recovered from the Antitoi’s, who picked it up from Gately’s partner in the DuPlessis robbery, or more likely, from Orin. Either way, they get a hold of it, which means that — as far as the standard plot progression goes — the “bad guys” actually win in the end of Infinite Jest.

THE ENTERTAINMENT ANTIDOTE — An Entertainment antidote may or may not actually exist. After looking through the book and the various interpretations online, I can only repeat what Marathe says: “Of this anti-film that antidotes the seduction of the Entertainment we have no evidence except craziness of rumors.”

MARIO INCANDENZA — Mario is fine.

So, then, what?

After the pages stop, Hal goes to the hospital, escaping the AFR who have come to ETA. He ends up in the bed next to Gately (previously occupied by Otis P. Lord), which is where Gately, Joelle, and Hal come together for the adventures ahead. John Wayne betrays the AFR to help in the search, and they try to dig up whatever is in JOI’s head — most likely the master copy of The Entertainment….

But it’s too late, Orin has already retrieved the master copy and sent a few out. He gives it to the AFR in exchange for his life/for not having roaches dumped on him…

The AFR uses The Entertainment to upend the current geo-political arrangement, ending subsidized time and the Gentle administration and starting some manner of military engagement. As someone better at putting clues together has pointed out, Hal mentions “some sort of ultra-mach fighter too high overhead to hear” in the first chapter. The AFR also does something to John Wayne, presumably something unpleasant, that prevents him from being at the WhataBurger tournament…

Hal’s condition worsens and he is unable to communicate, though he is still able to play tennis. He scares the administrators at his college interview and is sent to the hospital and etc.

Okay — so why, then, didn’t DFW just say so in the first place?

Well, for one, there was probably another 1,000 pages of action to write, which, if you think a mysterious ending is a lot to handle, I ask you to consider that alternative. There is also the fact that Wallace probably wanted to finish the way he’d been going for most of the book, by fracturing the narrative. Though in this case, it’s a full, if not clean, break. I’d also wager that he liked the idea of creating a loop, an endless entertainment, a novel with annular fusion. And whether he meant it to be or not, the “Back to Front” method of the book echoes Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, the apex of difficult fiction. Wallace was never shy about wanting fiction to be challenging; he wanted readers to be more than passive receptors of entertainment.

There are, I’m sure, many more defenses, but the last I’ll offer is this: The events that are left out are not what the book is really about. The continental emergency is not the thing to focus on or worry over. The final tying together of these anti-confluential narratives, this Byzantine pornography of characters, is not the goal. It doesn’t matter whether Gately and Joelle ever get together. Had Wallace “completed” the story, he would have distracted from what I think is the real meaning of Infinite Jest.

Stay tuned for Part 2, in which I’ll tell you what that is.

![]() September 19, 2012. What Happened? Pt. 2, pgs 3-1079.

September 19, 2012. What Happened? Pt. 2, pgs 3-1079.

Previously on “Words, Words, Words”:

Had Wallace “completed” the story, he would have distracted from what I think is the real meaning of Infinite Jest.

Stay tuned for Part 2, in which I’ll tell you what that is.

Commence Part 2…

So, I may have misspoke. The truth is that isolating a single “real meaning of Infinite Jest” is next to impossible. On one hand, it can be said that the novel is about many things: fathers and sons; mothers and sons; addiction; communication; entertainment; politics; greatness, mediocrity and failure. It’s a coming of age story alongside a recovery story that is also possibly a love story, all wrapped in a cloak-and-dagger-ish mystery about international realignment and terrorism. Choose your favorite combination and go with it. The book is about a lot of things.

On the other hand, it’s tough to say the book is actually “about” anything at all. As we have noted, there is no clear resolution. We never see the characters learn lessons, come of age, fall in love or be at peace in any way that warrants a Happily Ever After type of closure. The book literally stops far away and chronologically ahead of the main events in the novel (sort of) and we don’t entirely know who lives or dies, or what the shape of the continental borders look like, or whether fathers connected with sons. I’m sure many of the most frustrated readers have tossed up their hands and decided that Infinite Jest is really about nothing at all, some kind of post-modern experiment in reader-annoyance-tolerance-levels where we’re supposed to be thinking about what it means to read stories when really all we wanted was to just plain old read a story.

Rather than walking away from IJ in one of these two unsatisfying directions, it is possible to follow a third and potentially satisfying way.

I believe there is a unified theory of Infinite Jest that explains the various particles and waves of the novel — or most of them, at least — and helps clarify why Wallace made some of the choices he made. Be warned, however, that this theory drops deeper into Wallace’s other writings and his biography, and may not relieve the ailments of readers hoping for clarification on plot points. There’s also a good chance you will simply find this theory boring. But also note that IJ is just as enjoyable, in my opinion, with or without the ideas below.

The theory is this: Infinite Jest is Wallace’s attempt to both manifest and dramatize a revolutionary fiction style that he called for in his essay “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction.” The style is one in which a new sincerity will overturn the ironic detachment that hollowed out contemporary fiction towards the end of the 20th century. Wallace was trying to write an antidote to the cynicism that had pervaded and saddened so much of American culture in his lifetime*. He was trying to create an entertainment that would get us talking again.

You are advised to go and read “E Unibus Pluram,” but a quick and dirty rundown goes like this: television watching specifically (even in the relatively speaking “innocent” days of just a few dozen channels) and entertainment generally have occupied a startling portion of our lives and thus become a major, undeniable influence on How We Are. Watching television for an average of six hours a day (Wallace’s figure) means that people are functioning as passive receptors of entertainment for much, if not most, of their waking lives. And when our lives are filled with passive entertainment rather than active engagement with other humans, we are lonely. Also, because we tend to envision ourselves as the central characters in our own life-dramas/comedies, we imagine ourselves as being watched in the times when we are around other people. Thus, the average viewer’s “exhausive TV-training in how to worry about how he might come across, seem to watching eyes, makes genuine human encounters even scarier.” Therefore, more loneliness.

Now, TV didn’t invent human loneliness. Eleanor Rigby was darning her socks well before we got all these channels. But TV watching seems to interest Wallace in particular because it meets the criteria for an addiction — it creates/exacerbates a condition of loneliness and separation in its watchers, and then offers the cure in programming that plugs us into human communities and active lives being lived, though strictly as a watcher. Watching TV in excess leads to isolation and loneliness, but is also something very lonely people can do to feel less alone.

The way television deals with this apparent contradiction is to become a purveyor of a sardonic, detached, irony, and a self-referential, chummy knowingness. To keep us from feeling so lonely as constant watchers, TV had to convince us that it was our only friend, and the only place where we could get away from the slack-jawed pack of other humans and enjoy (passively) the company of clever, good-looking and like-minded people. The ultimate result was that shared sentiment was out; individual smugness and disapproval were in. TV watchers were convinced, through commercials etc, that they are not lonely because they spend so much time alone, but because they are unique, special, rebellious, misunderstood snowflakes, and are repeatedly comforted that they have transcended the herd mentality of their sheepish peers while they spend six hours a day as part of the largest group behavior in human history. Let me note, as Wallace does often, that this wasn’t malicious or sinister, but more of an organic response to keep viewers watching more and more TV.

As a fiction writer, Wallace was deeply concerned that fiction was unequipped to respond effectively to these trends. One reason he gives is that traditional forms of realism hadn’t kept up with a televisual world, and weren’t reflecting the reality of a new generation of readers. Another reason is that fiction could no longer parody the TV situation through irony. Irony, once a powerful and meaningful technique used by postmodern fiction (Barthes, Pynchon, DeLillo) to respond to and expose bad situations, had been co-opted by all the undercutting of real feelings and meaningless talk of “revolution” to advertise products on television. Fiction writers were trying to make us feel something — what Wallace famously described as “what it is to be a fucking human being” — in a setting where exposed feelings were regarded with, at best, skepticism and, at worst, scorn. So they fell back on old forms, or said next to nothing, and stuck to a cool and distant irony. But, as Wallace notes quoting Lewis Hyde, “Irony has only emergency use. Carried over time, it is the voice of the trapped who have come to enjoy their cage.”

Wallace wanted a fiction that acted as something more than a wry commentary on the emptiness of contemporary culture. As he wrote in “Fictional Futures and the Conspicuously Young” in 1988: “the state of general affairs that explains a nihilistic artistic outlook makes it imperative that art not be nihilistic.” The remedy for this unhappy detachment is what he called for two years later at the end of “E Unibus Pluram”:

The next literary “rebels” in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels, born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles. Who treat of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction. Who eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue. These anti-rebels would be outdated, of course, before they even started. Dead on the page. Too sincere. Clearly repressed. Backward, quaint, naive, anachronistic. Maybe that’ll be the point. Maybe that’s why they they’ll be the next real rebels. Real rebels, as far as I can see, risk disapproval. The old postmodern insurgents risked the gasp and squeal: shock, disgust, outrage, censorship, accusations of socialism, anarchism, nihilism. Today’s risks are different. The new rebels might be artists willing to risk the yawn, the rolled eyes, the cool smile, the nudged ribs, the parody of gifted ironists, the “oh how banal.” To risk accusations of sentimentality, melodrama. Of overcredulity. Of softness. Of willingness to be suckered by a world of lurkers and starers who fear gaze and ridicule above imprisonment without law.

One of the most pervasive and frustrating misconceptions about David Foster Wallace is that he is the voice of Generation X, we true geniuses of irony. I have more than once heard Infinite Jest described as an “ironic” book, if not the ironic book. People seem to think that Wallace wrote one thousand pages of careening sentences and fragmented narratives and endnotes with no true conclusion as some kind of ironic prank on readers, to make an epic novel that would punish you for reading. My impression is that Wallace made IJ difficult not only because he likes experimental, difficult fiction, but also because he wanted to force readers to engage. To do something that was harder and more active than just watching. If you sweep away all the bullshit expectations from IJ and just read the thing, it’s easy to see Wallace trying to fill the role of the new anti-rebel, with his single-entendre principles and plain old untrendy human troubles. Clichés hide brutally difficult truths about life. Addiction is bad; sobriety is good. Perfection is a myth. Brothers should be nice to each other. Entertainment can be addicting, lethally so, in this case. Unhappy parents make unhappy kids who become unhappy parents and so on.

For all the technical challenges, the stories in IJ follow these principles and are intended to act as the new kind of emotionally straightforward fiction Wallace desired. This is especially true regarding the Ennet House and Don Gately sections, which would have made a deeply moving recovery novel if taken alone without the rest of IJ.

But there is something else at work as well. The overall arc, or circle, of the novel also dramatizes the struggle of finding this new voice, one that can communicate in a way that is new and fresh, and yet still bring forward more “traditional” values.

Central to the dramatization is Hal Incandenza, who opens the novel by unnerving a panel of college administrators when he speaks to them. Hal, in his mangled voice, tries to tell the admissions panel things like

I have an intricate history. Experiences and feelings. I’m complex…

I’m not a machine. I feel and believe. I have opinions…

Please don’t think I don’t care.

This is quite a contrast from what Hal feels later in the book/earlier in the events about being basically empty of feeling:

Hal himself hasn’t had a bona fide intensity-of-interior-life-type emotion since he was tiny; he finds terms like joie and value to be like so many variables in rarified equations, and he can manipulate them well enough to satisfy everyone but himself that he’s in there, inside his own hull, as a human being — but in fact he’s far more robotic…inside Hal there’s pretty much nothing at all, he knows.

The admissions panel members respond to Hal’s admissions of feeling, by freaking out. They don’t understand Hal’s voice; they are, in fact, terrified by it.

It is no accident that this scene takes place at the University of Arizona, where Wallace met strong resistance when trying to write experimental stories that didn’t square with the institutional notions of good fiction practice. (Wallace points to this institutional generation gap in talking about a professor in the EUP essay, but there is a better, longer riff on the issue in MFA writing programs in “Fictional Futures.”)

Hal’s new voice is so mangled and unsettling that he ends up being hospitalized. It is when he is eventually asked “So yo then, man, what’s your story?” that the novel begins in earnest. By the last page of the narrative, when readers are compelled to head back to the first page (annular fusion), it’s clear that Hal has undergone a process that transformed him from an unfeeling and successful automaton or cipher** into a person with strong emotions, but who’s new voice makes it nearly impossible to communicate. Wallace doesn’t try to proscribe what that voice would exactly be like, only that it would be unsettling and challenging.

With this framework in mind, other connections between the essay and the novel come to light, with correlations that range from strong to weak to strange.

- The world of Infinite Jest: With its subsidized years, entertainer president and teleputers, this near-future is something Wallace had more or less predicted and discussed in EUP, saying, in short, that advances in TV technology are only going to enhance our dependence (i.e. addiction) to the isolated fantasies that technology provides. Wallace spins this out into a few fantastical but logical conclusions, like having our years up for advertising grabs, or the creation of an entertainment that is so addictive and narcotizing it kills its viewers.

- Mario Incandenza: Two years after the publication of Infinite Jest, Wallace wrote, “The best metaphor I know of for being a fiction writer is in Don DeLillo’s Mao II, where he describes a book-in-progress as a kind of hideously defective, hydrocephalic and noseless and flipper-armed and incontinent and retarded and dribbling cerebrospinal fluid out of its mouth as it mewls and burbles and cries our to the writer, wanting love, wanting the very thing its hideousness guarantees it will get: the writer’s complete attention.” Mao II was published in 1991, and the description it provides parallels the physical abnormalities and challenges of Mario Incandenza. Mario, if he is meant to model “the novel in progress” is also the most unjaded, childlike and shamelessly loving and friendly character in the book, i.e. an earnestly feeling human boy. Hal loves Mario, takes care of him, and is fiercely defensive of him. (There is also the story of Remy Marathe, whose wife bears a close resemblance to the description above and has become his reason for living.)

- The Anxiety of Influence: By the time he was writing Infinite Jest, Wallace had made a name as part of a generation of young fiction writers. He complains loudly, though optimistically, in the “Fictional Futures” essay about the station of his particular generation, one weighed down by marketing and high expectations, by MFA-program-manufactured standards of “good fiction,” and by the need to distinguish and establish their own voices and styles separate from their forefathers and -mothers. The novel he eventually wrote in response to this is fraught with generational tension, primarily those in which the young are torn between emulating and resisting the influence of their predecessors. The Hamlet references peeking through call attention to the good old Oedipal issues of both detesting and wanting to be your parent. It also allows Wallace to perform the concept he is writing about. James Incandenza’s alcoholic father — who has failed in the eyes of his own father — bullies JOI into playing tennis. JOI turns around and, himself an alcoholic, starts a tennis academy for his own son and others. Hal excels at tennis the same way his predecessors had, but once he starts speaking in own voice in the first-person chapters toward the end of the book, he debates whether he wants to play. JOI’s brilliance and experimental arts appears to represent a prior generation of experimental writers, the influences with whom the next generation must find a way to both converse with and surpass. Orin Incandenza stands as a failure to escape the shadow of his elders. Once a tennis player, he becomes a punter, a guy whose whole only job is to hand the ball over to the other team. It’s essentially a passive, uncreative role, and one that he excels at. A similar thing happens for Orin in the bedroom, where he is focused on pleasing his “subjects” but not himself, i.e. on being entertaining. Orin is so obsessed with his father that he eventually becomes little more than an imitator, the keeper of the Master Copy. By the end he is made to cheesily re-enact a scene from 1984, voicing nothing original at all. Finally, there is The Entertainment. James Incandenza created The Entertainment to try and draw Hal out of his isolation, to make sure he didn’t become a silenced figurant in his own life. He felt that Hal was going mute, and wanted to give him back a voice. But it didn’t work, and instead he made a movie so entertaining that it sapped the voice of anyone who watched it. This is, of course, the extreme version of what Wallace fears in EUP. It also fits into the ‘what you love in this life kills you’ half of JOI’s cosmology and the novel’s addiction narratives. The second part, about ‘what kills you mothers you in the next life,’ fits with the artistic development process in which a writer will emulate his or her influences and then, with effort and pain, abandon them to create a new voice. Something like that.

- The Tennis Styles: In “Fictional Futures,” Wallace wrote at length about the styles of fiction that had occupied the labors of his generation and the institutionalization via MFA programs of what made for “good” or “successful” fiction. John “No Relation” Wayne’s tennis abilities are reminiscent of the technically proficient writers who succeed in their own mechanical way, and his stark efficiency may even reflect Wallace’s objection to the cult of minimalism, or “Bad Carver” as he put it, in his generation’s writing. Mike Pemulis has a deadly and accurate lob, but has not developed his game beyond that one trick. Lamont Chu’s obsession with being a famous tennis player is preventing him from playing his best game. Troelstch is obsessed with giving commentary on other people’s matches. Schacht has resigned himself to not playing pro and wants to be a dentist. Substitute “writing” for “tennis game” and you have a list of common anxieties and behaviors in any American creative writing program. As for Hal, his tennis style is essentially no style. Being smart, seeing vulnerabilities and drawing his opponents into errors. Like Orin, he plays passively. Hal also worries that, after a rapid ascent, he has plateaued in his game. He must feel similar to, say, a young writer who published a celebrated novel he wrote as an undergraduate, and is stuck wondering if he will ever develop beyond his current level.

- Mark Leyner/Mike Pemulis: In EUP Wallace focuses his attention on image fiction author Mark Leyner and his book My Cousin, My Gastroenterologist, citing the jacket copy that calls the book “a fiction analogue of the best drug you ever took.” Leyner reacts to TV by fully absorbing and recreating it in fiction. Wallace’s analysis of the book is respectful of Leyner’s abilities and intelligence, but ultimately dismayed that it is does nothing. His discussion is also full of drug references: “methedrine compound of pop pastiche;” “bad acid trip;” “amphetaminic eagerness.” In a 1992 interview, Wallace referred to Leyner as “a kind of antichrist,” saying, “If the purpose of art is to show people how to live, then it’s not clear how he does this.” Michael Pemulis, Hal’s closest friend, is an extraordinarily capable and brilliant kid. He’s a smart-assed, prank playing math whiz who is the master of a game that simulates the end of the world. He is also the novel’s main source of drug knowledge and substance. As noted, his tennis technique he has one good trick, the high lob. Pemulis urges Hal to try more drugs in order to fix his unhappiness, which is roughly Lerner’s approach: Make fiction look more like television in order to get off the TV fix. In a 2003 interview, Wallace would refer to Pemulis as “one of the book’s Antichrists.”

If it seems strange to you that a person would write 1,000 pages of fiction to make a commentary on the state of fiction, it’s probably because you are a perfectly healthy and rational human being. But David Foster Wallace was not. Fiction was his vocation, his great love and his highest duty. Infinite Jest was also not the first time he wrote a long story about the development of his craft. The novella “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way” was about paying tribute to and dismantling meta- and avant-garde fiction. And before he came to dislike it, it was one of Wallace’s most prized accomplishments. Wallace was obsessed and engaged with fiction writing in the way that a professional athlete is obsessed and engaged with his or her own abilities. His obsession led to the kind of deep study and focus that led to Infinite Jest. But it also appears to have led to his ultimate unhappiness. Reading D.T. Max’s recent biography, it can be tedious to read how often Wallace writes to his friends about the status of his own output. It is difficult and, frankly, frustrating to watch his outward happiness track so closely to his happiness with his own fiction. This is a man who, according to many of the theories, took his own life because he believed he was unable to write powerful fiction any longer. The man who looked at the existing pages of The Pale King and determined they were not good enough to sustain him. Fiction was his great love, so he gave it the best thing he could think of: a story about itself, that is made up of the best fiction he could create, and helps sustain the enterprise for a new generation.

* Before going any further, let me say that — as with most things on this liveblog — I’m not the first or last to come up with the ideas I’m posting here. Samuel Cohen presents the idea of IJ as a “literary history” in his essay “To Wish to Try to Sing to the Next Generation: Infinite Jest‘s History,” which is collected in this year’s The Legacy of David Foster Wallace. D.T. Max, in his biography Every Love Story is a Ghost Story pegs the major writing efforts of Infinite Jest as beginning once Wallace articulated his ideas about what a new fiction should look like. And these are just the places where I’ve noticed people mentioning the connection. No reason to believe there aren’t plenty more. My plan here is to dive into this idea a little deeper and see what we come up with.

** Meaning “One having no influence or value; a nonentity.” But also appropriate as “the key to cryptographic system.”

![]() April 21, 2012. And But So Then?, pgs 958-981/1079. An AA story from someone it doesn’t appear we know takes up valuable pages in the few left before this whole thing comes to a close. No clues. No obvious ones anyway.

April 21, 2012. And But So Then?, pgs 958-981/1079. An AA story from someone it doesn’t appear we know takes up valuable pages in the few left before this whole thing comes to a close. No clues. No obvious ones anyway.

Then we get the story of the Middlesex A.D.A., who himself is a survivor, and whose wife has had a very hard time indeed after the Gately and co. toothbrush incident. Most importantly here, we learn that Gately is, legally at least, in the clear.

Then we are back at ETA, but not back inside Hal’s head. There are some indications as to what is happening in these pages at least. “Michael Pemulis was nowhere to be seen since early this A.M., at which time Anton Doucette said he’d seen Pemulis quote ‘lurking’ out by the West House dumpsters looking quote ‘anxiously depressed.'” Pemulis might have been searching for his discarded stash, but it’s hard to know for sure. Otis P. Lord returns briefly, but Poutrincourt is nowhere to be found. From the view overhead, Hal appears to be acting very strange: not eating his usual pre-match Snickers bar and asking Barry Loach (recently named the 10th best non-Hal or -Gately character in the book by Publishers Weekly) if “the pre-match locker room ever gave him a weird feeling, occluded, electric, as if all this had been done and said so many times before it made you feel it was recorded…[something about Fourier Transforms]…locked down and stored and call-uppable for rebroadcast at specified times.” This is similar to the feelings Hal had earlier, about how many times he had performed certain actions. Also like before, “[Hal’s] face today had assumed various expressions ranging from distended hilarity to scrunched grimace, expressions that seemed unconnected to anything that was going on.” And then five-and-a-half pages about Loach’s story and his salvation by Mario Incandenza.

After a long absence, we’re back with Orin, who, like the unfortunate roaches in his apartment from ~900 pages ago, is trapped under what appears to be a giant drinking glass. He’s been drugged and seems to have broken his good foot trying to kick his way out, and he seems genuinely confused about the meaning of the repeating announcement of “Where Is The Master Buried.” I always assumed Orin was the keeper of the Master, but this throws some doubt on that assumption. Speaking of roaches, a vent opens and begins to pour them into the enclosure, a la “1984.” Orin responds in kind, crying out “Do it to her! Do it to her!” Luria P—– is unamused, thinking of her fellow torturer as “a ham.”

Gately’s situation is not improving. His fever delirium has him half aware or less of what’s happening around him, though he knows that he is “the object of much bedside industry.” He hears his own head voice, with an echo, advise him to “never try and pull a weight that exceeds you,” and thinks to himself that he might die. The A.D.A. appears to be in the vicinity, no doubt struggling with the issues he discussed with Pat M. just a few pages ago. A voice at the door “laughed and told somebody else it was getting harder these days to tell the homosexuals from the people who beat up homosexuals.” It’s unclear if that has any relevance, except by a very circuitous inference that his hospital stay has revealed that Gately has AIDS and that AIDS is still considered a “homosexual” ailment in Wallace’s near-future. Not terribly likely. It appears that the dangerously feverish Gately is lifted into an ice bath, an experience that causes him to “wake up” back on the cold, piss-stained floor with Fackleman and Mt. Dilaudid.

The situation here is not improving either. A motley and highly unpleasant crew of people make their way into the luxury apartment, led by the always unwelcome Bobby C. Everyone starts ingesting extraordinary amounts of substances, aside from those people who are occupied with things like injecting other people with drugs or sewing Fackleman’s eyelids open. Bobby C has a recording of Linda McCartney’s isolated vocals that he apparently loves, which, I mean really, the guy is just rotten to the core. And yet, he is gentle with Gately as they inject him with liquid sunshine and his senses inflame and he begins to tumble to the ground. The endnotes here contain more than one reference to missiles. For Gately, the experience on the whole is “obscenely pleasant.”

And when he came back to, he was flat on his back on the beach in the freezing sand, and it was raining out of a low sky, and the tide was way out.

Before you get angry, at least consider that, for what it’s worth, the imagery here has Gately out of the water and into the cold — contrary to the warm, liquid womb-type imagery from before when he was on drugs.

Now you can feel free to embrace your frustration, and Google “What happened at the end of Infinite Jest,” and head back to the front of the book. If you’ve enjoyed yourself so far, though, take heart. You’re just getting started.

![]() April 14, 2012. Byzantine Pornography, pgs 934-958/1078-1079. A brief moment in which Joelle van Dyne is picked up by Hugh/Helen Steeply pulls us out of Gately’s fever memories. But we’re quickly back in, as Gately and Fackleman descend further into their binge, watching JOI’s Kinds of Light, pissing themselves and being just all around pretty disgusting. Even still, rolling M&Ms through urine, then actually shooting up with urine instead of water is arguably less disgusting than Pamela Hoffman-Jeep’s “standard anti-hangover breakfast” the Phillips Screwdriver made of vodka and Milk of Magnesia. It’s accurately described by Gately as a “lowball.” Within the space of a few pages we catch a few missile references: “he [Gately] might as well have been strapped to the snout of a missile” and “it became the ICBM of binges,” indicating that there may be some “Gravity’s Rainbow” overtones here. A later reference, during Hal’s section, to a “sad and beautiful Aryan-looking boy” adds to the presence of GR in these pages. As things get worse and worse for Gately and Fackleman (who has now shit his pants), Gately reverts more and more to his childhood of the breathing ceiling and the bars of his playpen.

April 14, 2012. Byzantine Pornography, pgs 934-958/1078-1079. A brief moment in which Joelle van Dyne is picked up by Hugh/Helen Steeply pulls us out of Gately’s fever memories. But we’re quickly back in, as Gately and Fackleman descend further into their binge, watching JOI’s Kinds of Light, pissing themselves and being just all around pretty disgusting. Even still, rolling M&Ms through urine, then actually shooting up with urine instead of water is arguably less disgusting than Pamela Hoffman-Jeep’s “standard anti-hangover breakfast” the Phillips Screwdriver made of vodka and Milk of Magnesia. It’s accurately described by Gately as a “lowball.” Within the space of a few pages we catch a few missile references: “he [Gately] might as well have been strapped to the snout of a missile” and “it became the ICBM of binges,” indicating that there may be some “Gravity’s Rainbow” overtones here. A later reference, during Hal’s section, to a “sad and beautiful Aryan-looking boy” adds to the presence of GR in these pages. As things get worse and worse for Gately and Fackleman (who has now shit his pants), Gately reverts more and more to his childhood of the breathing ceiling and the bars of his playpen.

We now appear to be alternating between Gately and Hal and Joelle, who is now describing The Entertainment — and the location of the master cartridge — under USOUS questioning. Just as it is for USOUS, this interview is evidence for us readers to help piece together exactly what the hell is happening.

Hal returns to his room to find Coyle and Mario and some developments in the events around ETA. Apparently Lateral Alice Moore arranged the switch for Axford and Troeltsch, and I suspect there’s not much more to this seemingly significant and perhaps light-shedding turn of events than to embed and heighten in us as readers Hal’s feeling “that something as major as a midterm room-switch could have taken place without my knowing anything about it filled me with dread.” Which is pretty goddam brilliant of old DFW. Coyle tells Hal about Stice’s theory that a ghost is haunting him to raise his game, and Hal futher theorizes “Or hurt somebody else’s.”

Coyle is watching JOI’s Accomplice! which again sparks Hal’s interest in his father’s intentions. Accomplice! appears to be another odd JOI joint, focused on a meta-watching experience. Hal mentions “a self-conscious footnote” and explains that the film’s “essential project remains abstract and self-reflexive; we end up feeling and thinking not about the characters but about the cartridge itself.” Its star, Cosgrove Watt, is first spotted by JOI in a commercial wearing a white toupee, just like JOI Sr. wore and just like Lenz wears. Graduate students start your engines on that one. Speaking of which, Hal watching the reports of snow falling on various people and places across the area, and his calling up of the phrase “smiling mirthlessly,” brings to mind James Joyce and his story “The Dead.” I’ll go ahead and make too much of it by pointing out Hal’s observation that “I had never once ridden a snowmobile, skied, or skated: E.T.A. discouraged them. DeLint described winter sports as practically getting down on one knee and begging for an injury” (emphasis mine, since this basically what happens at the end of “The Dead,” except with love and not with winter sports).

Hal begins to reminisce. The poster he remembers of Lang directing Metropolis is, presumably, the one Wallace wanted to use as the cover of the book. He remembers seeing a knife stuck in a mirror, though not the word KNIFE written on a non-public mirror. Hal’s impression of the Byzantine erotica he was once interested in feels like the organizing idea for all of IJ: “Something about the stiff and dismantled quality of maniera greca porn: people broken into pieces and trying to join, etc.” He realizes he doesn’t want to play anymore, and thinks about injuring himself to avoid ever playing again and “becoming the object of compassionate sorrow rather than disappointed sorrow.” It’s another moment in this book that is harder to read knowing the author’s fate. Hal recalls a sad moment involving Himself, Orin and pornography’s impoverished idea of sex, and he thinks about his mom. He knows about John Wayne, as well as a long list of others including Marlon Bain. He pictures Wayne and his mom in what is presumably a posture of the Byzantine porn.

Joelle comes back to “the House” to find a Middlesex County Sheriff’s car sitting outside.

![]() April 5, 2012. Too Late, pgs 911-934/1077-1078. We’re back with old Don Gately, lying in his hospital bed. It doesn’t seem like Gately’s been put on pain-killers, but he does keep returning to memories of Gene Fackleman, who was first brought to mind when the MD suggested the use of Dilaudid. Also, it seems like just about every MD in Wallace’s near-future imaginings is South East Asian or Near/Middle Eastern. We’re pretty well embedded into Gately’s memories/fever dreams at this point, and as the pages slip by we are, for something like the first time in 911 pages, deeply engaged in a self-contained linear narrative.

April 5, 2012. Too Late, pgs 911-934/1077-1078. We’re back with old Don Gately, lying in his hospital bed. It doesn’t seem like Gately’s been put on pain-killers, but he does keep returning to memories of Gene Fackleman, who was first brought to mind when the MD suggested the use of Dilaudid. Also, it seems like just about every MD in Wallace’s near-future imaginings is South East Asian or Near/Middle Eastern. We’re pretty well embedded into Gately’s memories/fever dreams at this point, and as the pages slip by we are, for something like the first time in 911 pages, deeply engaged in a self-contained linear narrative.

We take a quick break to find out that Pemulis’ stash has been raided, though he still goes looking in his hiding place for something. This section also marks the unhappy return of Bobby C, or just C, from the very early yrstruly chapter where he meets his painful but not exactly undeserved fate.

When Gately comes to he once again feels like “he was trapped inside his huge chattering head,” which brings him back to all sorts of unpleasant feelings about being a helpless child. He refers to himself as a figurant, and thinks of “the wraith’s nonexistent kid.” Speaking of figurants, Gately slips back into a memory/dream about his pseudo-romance with Pamela Hoffman-Jeep, “his first girl ever with a hyphen” and “the single passivest person Gately ever met.” The pages are rife with Gately as caretaker and protector, if we weren’t already aware of that by now. Hoffman-Jeep falls for Gately because he does nothing. While she is telling Gately the story of Fackleman’s fuck-up and impending doom, Gately notes that “Like most incredibly passive people, the girl had a terrible time ever separating details from what was really important to a story.” Kinda hard not to sympathize as we slouch towards the final pages and the only thing that obviously ties together the threads of the previous 930 pages is that they’re not connected to what’s going on in the story now.

BUT THEN…Gately wakes up to see the wraith and a wraith-Lyle licking the sweat off his forehead. HIs attempt to swing at them sends him back into pain-delirium where, in addition to a Buddhist-heavy mirror-wiping dream and one consisting of only “the color blue, too vivid, like the blue of a pool,” he sees himself with a “very sad kid” digging up some dead guy’s head. Joelle van Dyne is there, and Gately feels like he knows the guy they’re digging up. When they get there it looks like the sad kid yells out “Too late.”

And if you’re curious why this liveblog is taking so long, one reason is that this happens every time I try to read:

![]() March 29, 2012. Using Your Head, pgs 902-911/1077. Many questions in just a handful of pages. We continue to get Gately’s backstory, which is kind of funny in a you-don’t-get-the-backstory-of-a-major-character-until-the-last-hundred-pages kind of way. We establish that Gately was nine years old during what sounds like the Rodney King riots. Assuming Wallace is referring to these specific riots, that means Gately was nine in March of 1992, and is 29 here in the YDAU, making it 2011 or 2012. It’s unclear when his birthday is, though I’m sure some enterprising young obsessive could figure it out. For not, it’s another clue in nailing down the exact year.

March 29, 2012. Using Your Head, pgs 902-911/1077. Many questions in just a handful of pages. We continue to get Gately’s backstory, which is kind of funny in a you-don’t-get-the-backstory-of-a-major-character-until-the-last-hundred-pages kind of way. We establish that Gately was nine years old during what sounds like the Rodney King riots. Assuming Wallace is referring to these specific riots, that means Gately was nine in March of 1992, and is 29 here in the YDAU, making it 2011 or 2012. It’s unclear when his birthday is, though I’m sure some enterprising young obsessive could figure it out. For not, it’s another clue in nailing down the exact year.

Gately’s relationship to his head, at least in his younger days, is far different from the way Wallace usually deals with heads. Gately’s is a tool, a physical object so large and indestructible that it serves as a net positive in his social interactions and overall happiness. Most of the other heads in this book are portrayed as something along the lines of locked cages and/or torture instruments. The “here” from Hal’s “I am in here.” on the first page of the book is reasonably interpreted as inside his head. It’s the first of many times when someone is basically trapped by their head — but not the young Don Gately, who uses his head to get laughs, get beers and get touchdowns. For more on how Wallace felt about heads, check his Kenyon University remarks.

Speaking of being inside Hal’s head, we swing back to another of his first person sections. “Some more heads came and awaited response and left.” This section marks the return to the main text of Mike Pemulis, who appears looking haggard. When Hal says “I could see my asking him where he’d been all week leading to so many different possible responses and further questions that the prospect was almost overwhelming,” it sounds an awful lot like the way being high has been described earlier in the book.

As I said, there are many questions, for example…

Pemulis says that Petropolis Kahn, who Hal appeared to ignore a moment ago, had “mentioned hysterics” when reporting to MP about Hal being in the room. Hysterics?

Hal is thinking of his father’s funeral. Why?

There is “a whoop and two crashes directly overhead.” Significant? Or just general ETA-waking-up noises?

There is what seems to be a deliberate mention that Hal hasn’t seen C.T. or his mom all week. Where are they?

When asked about going to get food off campus, Hal finds that “I couldn’t decide.” Hamlet Sighting? (Yes.)

When Hal says that Pemulis “blarneyed” the urinalysis guy into giving them 30 days, Pemulis, who is itching to talk to Hal about something important, replies “Blarney wasn’t why we got it, Inc, is the thing.” Why did they get it, then?

Pemulis remarks that he hasn’t even heard of half of JOI’s stuff, followed by “And me using the poor guy’s lab.” What is Pemulis using the lab for?

Pemulis misreads that Annular Fusion is Our Fiend, and is corrected by Hal that it’s our Friend.

The closing of the section focuses on JOI’s film Good Looking Men…etc, with Hal specifically requesting to watch the last part in which Paul Anthony Heaven delivers a pedantic lecture on ancestors and inherited behaviors. When JOI enters the pages I always consider him as a stand in for Wallace, or at least Wallace’s artistic ambitions, and here we have his work appearing as Pemulis wears rimless specs and talks about blarney, while Hal considers the insertion of references to the artists JOI loved while the lecturer refers to generational hydrophobia. These cues make me think of James Joyce, and may perhaps explain Wallace’s struggle to avoid being “deprived of some essential fluid, aridly cerebral, abstract, conceptual, little more than hallucinations of God,” and step out of the shadow of his ancestor: “it is, finally, artistic askesis[discipline, or asceticism] which represents the contest proper, the battle-to-the-death with the loved dead.”

…tears run down Heaven’s gaunt face…

Last question: The book ends in 70 pages. How is he going to wrap this up?

![]() March 22, 2012. When it Comes, pgs 883-902/1077. We are now into a repeating Gately-Hal cycle. Gately wakes up with the sound of “sandy sound of gritty sleetish stuff” against his room window, which means it may be in the same timeframe as Hal’s morning with the snowstorm. He attempts to argue with his M.D. — a cheerfully sinister South East Asian who echoes the Near Eastern Medical attaché. As the M.D. offers up possible painkillers, “Gately imagines the M.D. smiling incandescently as he wields a shepherd’s crook,” recalling Gately’s painfully obvious dream about relapse. When the M.D. gets around to recommending Dilaudid, Gately thinks of his old crew-mate Gene Facklemann. There are more womb images appearing here and there as well. “Pentazocine lactate is Talwin, Gately’s #2 trusted standard when he was Out There, which 120 mg. on an empty guy was like floating in oil the exact same temperature as your body” and “The thing about Demerol wasn’t just the womb-warm buzz of a serious narcotic.” Gately also continuously refers to his resistance as “not-Entertaining,” which with the capital-E on there on more than one occasion seems hardly coincidental. When McDade and Diehl show up, Gately wants to know what day it is: “That Gately can’t communicate even this most basic of requests makes him want to scream.” Which sounds familiar.

March 22, 2012. When it Comes, pgs 883-902/1077. We are now into a repeating Gately-Hal cycle. Gately wakes up with the sound of “sandy sound of gritty sleetish stuff” against his room window, which means it may be in the same timeframe as Hal’s morning with the snowstorm. He attempts to argue with his M.D. — a cheerfully sinister South East Asian who echoes the Near Eastern Medical attaché. As the M.D. offers up possible painkillers, “Gately imagines the M.D. smiling incandescently as he wields a shepherd’s crook,” recalling Gately’s painfully obvious dream about relapse. When the M.D. gets around to recommending Dilaudid, Gately thinks of his old crew-mate Gene Facklemann. There are more womb images appearing here and there as well. “Pentazocine lactate is Talwin, Gately’s #2 trusted standard when he was Out There, which 120 mg. on an empty guy was like floating in oil the exact same temperature as your body” and “The thing about Demerol wasn’t just the womb-warm buzz of a serious narcotic.” Gately also continuously refers to his resistance as “not-Entertaining,” which with the capital-E on there on more than one occasion seems hardly coincidental. When McDade and Diehl show up, Gately wants to know what day it is: “That Gately can’t communicate even this most basic of requests makes him want to scream.” Which sounds familiar.

Hal has gone from feeling and apparently acting a little funny to having a full physical reaction. “I was moving down the damp hall when it hit.” He’s perceiving things very intensely and thinking about his accumulated days walking down the halls of ETA in all “kinds of light.” Lying on his back in Viewing Room 5 he thinks about how “if it came down to a choice between continuing to play competitive tennis and continuing to be able to get high, it would be a nearly impossible choice to make.” Hal mentions that the attendant at the Shell Station last night had recoiled from him, meaning that his weird faces and such might have started the night before. Apparently John Wayne had been taken to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital after his encounter with the Tenuate, which means he could have been the person crying with the deep voice next to Gately. But that seems unlikely since Gately says he could tell the shot the man was getting was narcotic. Hal has a sort of teenager-type revelation/recurring DFW theme that “We are all dying to give our lives away to something” and follows up with a literal Hamlet sighting. Tavis’ biological father was killed in a freak accident playing competitive darts, and his mother was at least partly homodontic like Mario. While Gately’s thinking about wombs, Hal lays in his “tight little sarcophagus of space.”

![]() March 14, 2012. Tragedy Comedy, pgs 865-883/1077. Hal, still in first person, goes to brush his teeth. The early morning crying he hears behind closed doors reminds me of the stories I’ve heard from people who were in Teach for America: “Lots of the top players start the A.M. with a quick fit of crying, then are basically hale and well-wrapped for the rest of the day.”

March 14, 2012. Tragedy Comedy, pgs 865-883/1077. Hal, still in first person, goes to brush his teeth. The early morning crying he hears behind closed doors reminds me of the stories I’ve heard from people who were in Teach for America: “Lots of the top players start the A.M. with a quick fit of crying, then are basically hale and well-wrapped for the rest of the day.”

For some reason, the clock in the bathroom reads “11-18-EST456” when the day is actually the 20th. Maybe it’s an uncorrected effect of ETA’s fixing of the mirrors to prevent Pemulis from messing with them. Maybe it’s something else. I like to think that the snow on the boys’ dorm windowsill is a basically meaningless but polite nod to “The Catcher in the Rye.”

Hal wanders out to find Ortho Stice chanting to himself. His forehead is frozen to the window, facing outward much like a night watchman, as a previous commenter has pointed out while posing a pretty compelling theory that this is the point at which the narrative begins to line up with the narrative of Hamlet.

Whatever the case is, strange things are all around. There is a figure outside sitting on the bleachers in the snow. Ortho tells his story about waking up in the middle of the night and slips and says “The point’s I’m up there —” about his bed. Troeltsch and Axhandle have either switched rooms or are in the same room on the same twin bed. The Darkness then asks if Hal believes “in shit” like ghosts. He mentions that someone came by before but just stood behind him silently, “Then he went away. Or…it.” Ortho tells Hal that if he pulls him off the window, “I’ll take and show you some parabnormal shit that’ll shake your personal tree but good,” referring to his bed moving around in his room. Stice won’t come unstuck from the window.

Hal goes for help, taking his toothbrush with him because of a previous incident at ETA in which students’ brushes had been dosed with Betel nut extract. Kenkle interrupts a monologue on sex — which sounds an awful like the description of a beast with two backs — to greet “Good Prince Hal.” Hal explains the situation to them and Kenkle asks him why it’s so funny. He appears to be laughing.

A yell sounds from upstairs.

Then — the US Office of Unspecified Services is preparing for a release of The Entertainment, with market tested ideas on how to reach little kids. It’s an interesting idea but feels like a bit of a distraction from the events unfolding with people we really care about. There is one interesting point of note, a connection to way back on page 419, when Marathe is thinking about the “latent and sadistic” assignments USOUS gives to its operatives. One of the things he lists is “healthy women as hydrocephalic boys or epileptic public-relations executives.” In this scene 460 pages later, Carl E. (‘Buster’) Yee, Director of Marketing and Product-Perception at the Glad Flaccid Receptacle Corporation, has an epileptic fit in the middle of the meeting. And I won’t even venture any unwelcome speculation about hydrocephalic boys.

*Maybe it’s crazy to look for such deliberate clues. It’s as stupid as trying to find “Hamlet” in Pi — unless…

.

Happy Pi Day everybody!

![]() March 8, 2012. Alas, Poor Tony, pgs 845-864/1076-1077. Finally, the end comes for Poor Tony Krause and Randy Lenz, two of the most unpleasant characters I’ve had the pleasure of reading.

March 8, 2012. Alas, Poor Tony, pgs 845-864/1076-1077. Finally, the end comes for Poor Tony Krause and Randy Lenz, two of the most unpleasant characters I’ve had the pleasure of reading.

Lenz remains Lenz right up to the very end, apparently cutting Krause’s digits off and offering them up during the AFR civilian testing of The Entertainment. If there was any ambiguity, it seems that Marathe has definitely made his choice since he failed to report Jolene’s presence to Fortier and “had made his decision and his call,” said call being to Steeply. In the meantime, he helps plan an AFR incursion to ETA to get at Hal, Mario and Avril.

Gately dreams. He’s with Joelle getting ready for romance when her revealed face is that of Winston Churchill. This is reminiscent of the description of Ortho Stice from two hundred and ten pages prior: “A beautiful sports body, lithe and tapered and sleekly muscled, smooth…on whose graceful neck sits the face of a ravaged Winston Churchill, broad and slab-featured…” It’s too far a stretch for me to call this a Hamlet Sighting, but I do think it’s funny that there is some possibly family resemblance between our possible Laertes and our almost certainly Ophelia characters. The root cause, however, is most likely David Foster Wallace’s feeling that Winston Churchill was funny looking. Gately’s touching memory-dream of Mrs. Waite morphs into what appears to be the content of The Entertainment, in which JOI’s death/female/mother cosmology is explained to Gately, who submits to it.

Hal wakes from a dream and — for what I think is the first time — speaks in a first person voice that is loudly and clearly identified as Hal (and not just a random, nameless first-person somewhere in the jumble of characters in the previous 850 pages). Hal now has a voice, and it’s one of the coolest tricks in a tricky novel, mostly because it doesn’t feel like a trick. Pemulis is off the stage, but he’s clearly on the mind of Hal, who describes the snow outside as “Yachting-cap white.” He is then struck by that fact that he’s having feelings of not wanting to play tennis: “I couldn’t remember feeling strongly one way or the other about playing for quite a long time, in fact.” Hal is shifting out of neutral, which seems like a good thing, but is also accompanied by the feeling that “without some one-hitters to be able to look forward to smoking alone in the tunnel I was waking up every day feeling as though there was nothing in the day to anticipate or lend anything any meaning.”

Gately wakes up to the real Joelle van Dyne. Like her Ennet House-mates, Joelle unloads her recovery narrative on Gately, only this time he doesn’t seem to mind. He takes inspiration from her progress and has his own kind of breakthrough: “He could do the dextral pain the same way: Abiding.” We hear a by now familiar Wallace refrain “What’s unendurable is what his own head could make of it all.” All this business about living in the moment and ignoring the mind carries more-than-subtle notes of Buddhism.

In addition to refusing narcotic painkillers, Gately also tries to convince himself to swear off Joelle.

![]() March 2, 2012. Images, N/A. With apologies for the slow pace of recent post — this damn day job is really cramping my style — here are some images to keep you busy.

March 2, 2012. Images, N/A. With apologies for the slow pace of recent post — this damn day job is really cramping my style — here are some images to keep you busy.

A police sketch built on descriptions of Hal Incandenza in the book. This was originally on The Composites, a cool site where you can find more of your favorite literary characters pictured as if they robbed a local convenience store and are still at-large. However, Hal’s image has been removed for reasons that are unclear.

And then, from Brain Pickings, “3 Ways to Visualize the David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest” (sic). A flowchart, a geolocation photo tour, and a character diagram.

PS — You can buy this one here (five over, four down).

Finally, an oldie but goodie from The Boston Globe:

![]() February 25, 2012. “….”, pgs 809-845/1076. Gately is laid up in the trauma wing of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, mute and only non-narcotically medicated. As such, he has become a target for Ennet House visitors eager to unload their memories, and for his own mind to unload a few of his own memories as well. Tiny Ewell is first, along with a “tall and slumped ghostish figure” and “the blurred seated square-head boy” who is likely to be Otis P. Lord with the computer monitor still stuck over his head. Ewell’s story of his school boy days makes him sound quite a bit like an early Mike Pemulis. Gately keeps dreaming about “Orientals” for some reason that I can’t identify.

February 25, 2012. “….”, pgs 809-845/1076. Gately is laid up in the trauma wing of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, mute and only non-narcotically medicated. As such, he has become a target for Ennet House visitors eager to unload their memories, and for his own mind to unload a few of his own memories as well. Tiny Ewell is first, along with a “tall and slumped ghostish figure” and “the blurred seated square-head boy” who is likely to be Otis P. Lord with the computer monitor still stuck over his head. Ewell’s story of his school boy days makes him sound quite a bit like an early Mike Pemulis. Gately keeps dreaming about “Orientals” for some reason that I can’t identify.

Gately talks about the “airless and hellish, horrid” condition of being unable to speak and it seems that, as we approach the final pages of the book, both of our main protagonists are fighting the temptation to take drugs. Hal sees faces in the floor and Gately sees breathing in the ceiling. Gately’s bed is moved like Stice’s and he ends up next to a crying patient with a very deep voice. No clue who that is.

Enter ghost. The figure that has been resting its tailbone on the window sill (like JOI’s mother in previous scenes) is JOI Himself. The Hamlet Sightings are off the charts here, with the se offendendo that Wallace notes in the endnotes to JOI being the ghost of Hamlet’s father to his insertion of the word LAERTES into Gately’s thoughts. Bear in mind also that Laertes is the father of Odysseus, so there may even be some James Joyce/Homer sightings taking place here as well. We learn from the ghost of JOI about figurants, and how he felt like one his entire life and how Hal had started to become one just before JOI’s se offendendo. The figurants conversation also offers a hefty justification for why this book pretty much features “every single performer’s voice, no matter how far out on the cinematographic or narrative periphery they were.” Immediately the early Clenette chapter (“Wardine say her mama aint treat her right…”) comes to mind.

We learn that the purpose of The Entertainment was for JOI to connect with Hal, “To bring him ‘out of himself,’ as they say. The womb could be used both ways. A way to say I AM SO VERY, VERY SORRY and have it heard. A life-long dream. The scholars and Foundations and disseminators never saw that his most serious wish was: to entertain.” I’m not certain of the exact timeline here, but it seems possible that JOI-as-wraith might be able, at some point during these interactions with Gately, to whisk up the hill to ETA and see his son actually watching and presumably being entertained by his father’s movies.

Gately slips in and out of consciousness, remembering the MP who abused his mother.

![]() February 21, 2012. DFW: 1962-2008

February 21, 2012. DFW: 1962-2008

He would have been 50 today.

![]() February 16, 2012. Subsequent Events, pgs 785-808/1066-1076. Rather than taking Pemulis’ advice to try something new, Hal visits Ennet House to try and get information on meetings to help him kick the habit he won’t call an addiction. It’s a quick section, but Wallace does a nice job of being Johnette Folz and seeing a well established character through the eyes of someone who doesn’t know him and doesn’t particularly care about him.

February 16, 2012. Subsequent Events, pgs 785-808/1066-1076. Rather than taking Pemulis’ advice to try something new, Hal visits Ennet House to try and get information on meetings to help him kick the habit he won’t call an addiction. It’s a quick section, but Wallace does a nice job of being Johnette Folz and seeing a well established character through the eyes of someone who doesn’t know him and doesn’t particularly care about him.

Molly Notkin is spilling the beans in the decidedly less-strenuous variety of technical interview performed by the U.S.O.U.S. We get more important details about The Entertainment and Joelle’s history. These revelations include: JOI’s death/female cosmology; two kitchen appliance related suicides; sordid implications that Avril Incandenza was involved in both a sordid relationship with Orin and the sordid details of JOI’s suicide; the story of Joelle’s weird father and the alleged disfiguration that keeps her veiled. All of this seems very enlightening and settling of certain questions until Notkin* tells her interviewers that “Madame Psychosis’s name was in reality Lucille Duquette,” at which point we realize that any of the other details might be lies or exaggerations as well.

Then Hal heads out to an unspecified anti-substance meeting, but not before he “rushed through P.M.’s dispatching Shaw 1 and 3 by the time the regular P.M.’s were even warming up” — which indicates that Hal may be getting his tennis chops back at least. The meeting turns out to be one of the more absurd and horrible things in the book (and this is right after a section in which a woman has been described killing herself with a kitchen sink garbage disposal), where we get a look at at least one variety of feral infant. I’ll sum it up the way Wallace sums up the section: